Londinium, Lundenwic, Lundenburh, London. Different names for the same place. At least, such was the belief until the late 20the century, when archaeologists could report that the history of the settlement at the River Thames was much more complex. New studies by the archaeologist, Victoria Ziegler explores this.

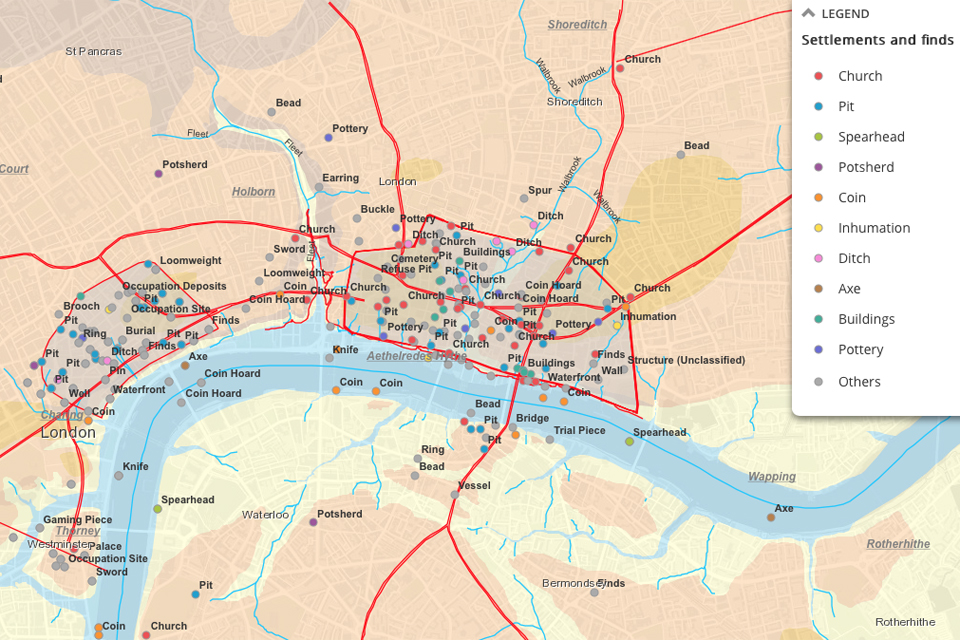

Londinium was during the Roman occupation of Britain a proper civitas surrounded by impressive and forbidding Roman walls. Until the late 20th century, historians and archaeologists believed that this “city” was then as now the heart of London. In 1984, excavations near the Covent Garden area, however, revealed the location further up the river of the Anglo-Saxon trading settlement, known as Lundenwic. Hereafter, it was evident that Lundenwic and Lundenburh in Anglo saxon time were two geographically distinct settlements.

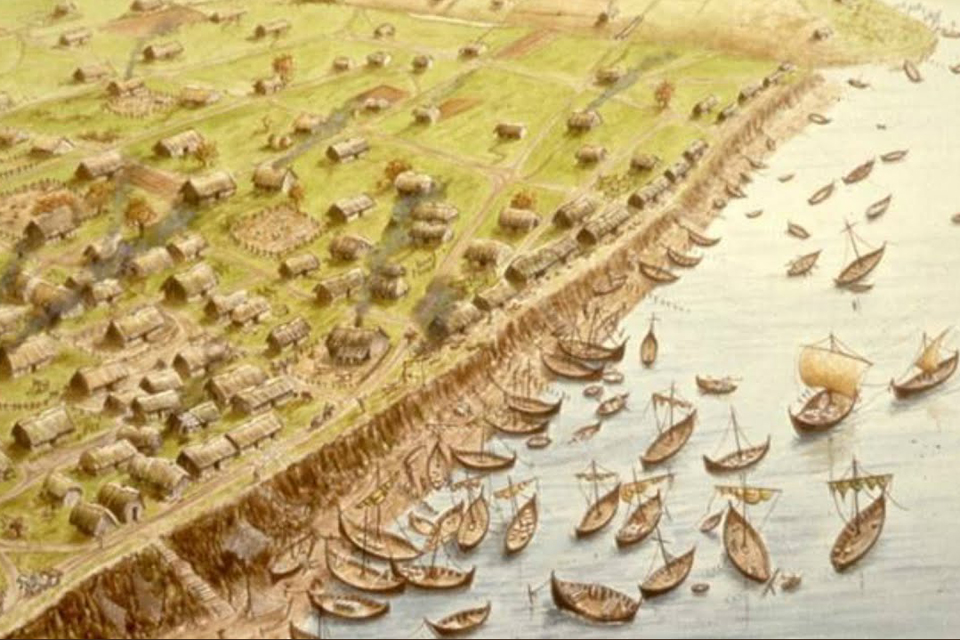

Excavations have since shown that Lundenwic was settled c. 600, and soon grew into a significant trading place, the heyday of which can be dated c. 700 – 750. But archaeologists have also been able to demonstrate that the occupation of Lundenwic ceased before c. 850, when activities moved to Lundenburh (the original Londinium). Until then, the old Roman civitas had been relatively void of activity.

Written sources confirm this. Between AD 604 and 850, chronicles would refer to the wic, the vicus, or portus, with wic or vicus broadly referring to a small settlement, and portus, of course, to the harbour on the River Thames. Bede, would famously describe it as “an emporium for many nations, who come to it by land and sea” 1).

After 857, this shifted, when the last reference to “vico Lundoniae” can be detected. Afterwards, the settlement was referred to as “Lundenburh”. Enticingly, the first reference to this “new location” can be found in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in connection with the Viking attack in 851, according to which 350 ships sailed up the Thames and plundered the town.

In a recent article, the archaeologist, Victoria Ziegler has explored what exactly took place at this crucial point in history. By studying in detail the archaeological assemblages at both the wic from c. 770 – 850 and the burh from c. 850 – 950, she has uncovered fascinating information about the occupational identities in London between 770 and 950; and the tentative outline of shifting focus from a trading to an administrative centre.

In short, 79 “different categories of archaeological assemblages were identified”, she writes, thus moving on to characterise the two settlements.

First of all, she has discovered that Lundenwic was settled with proper buildings, surface-laid houses, while later Lundenburh was dominated by sunken-floored buildings. Further, she found that crafts played a significant role in the activities in the wic. On all parameters from textile, horn, antler, leather and iron working, to butchery and grain processing, the wic appeared as a proper town. Also, imported pottery and glass vessels signified the commercial character of the activities there, as did the combs, brooches, and beads found in the excavations. The assemblages studies by Ziegler demonstrates that the wic was a thriving commercial hub until c. 850.

The later burh, on the other hand, surfaced as a place where people to a lesser degree pursued crafts or consumed imported pottery or glass vessels. On the other hand, they seemed to have dressed in imported luxury textiles, and sported more “personal items” made of glass and ivory. Another find, moneyers’ dies, indicate a more civic role of the old “city”.

It is tempting to understand the two 8th century settlements as complementary, with the wic as the primary trading and craft centre, while the Burh played the role as the location for ecclesiastical communities and a mint etc. The present study cannot confirm this conclusion, though, as the study also revealed a distinct cultural and practical overlap between the two settlements; perhaps mirroring the gradual movement to the burh of the inhabitants of the wic, while the burh kept its original role as the locus for the administrative and religious centre in the region.

It is likely, future studies of the social structure of the burh (parishes, churches, religious institutions) as well as toponymic studies might provide a more detailed historical context for the evidence, with which the archaeological assemblages presented here by Victoria Ziegler provides. And hopefully offer us even more insights as to what took place in the crucible of the early medieval city of London, c. 850 – 1000.

NOTES:

1) Bede: The Ecclesiastical History of the English people.

Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Judith McLure and Roger Collins.

Oxford University press 1994. Ch. II.3., p. 73.

SOURCE:

From wic to burh: a new approach to the question of the development of Early Medieval London

By Victoria Ziegler

In: Archaeological Journal, 01.03.2019

Victoria Ziegler is currently working at the University of London on a “a study of urban trans-location in early medieval England: occupation identities in Saxon London 770-1020”. In 2018, she received the Royal Archaeological Institute’s Master’s Dissertation prize. The publication of the present paper, is part of the award.

READ MORE:

London – Map

From Mola.org