Geoffrey de Charny was not only the first documented owner of the Shroud of Turin. He was also an accomplished knight, who wrote a famous handbook of Chivalry

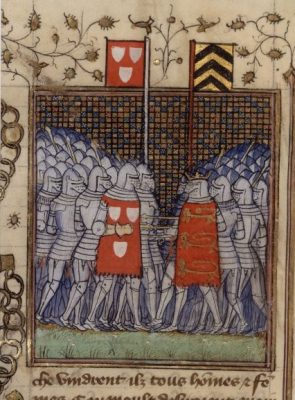

One of the more famous participants in the Hundred Years War was a French knight, Geoffrey de Charney, who died at the battle of Poitiers in 1356 clutching the Oriflamme (the sacred banner of the Kings of France) in his hands. Intensely pious, he is the first documented owner of the Shroud of Turin (although he probably regarded it as an icon and not a relic). But he was also the author of at least three treatises on chivalry. To say the least, he is one of the very poignant representatives of the chivalric knight and thus deserves a closer look.

Early Career

No exact date of birth is known for Geoffrey de Charny. However, he must have been born before (or perhaps) during the death of his mother in 1306. The family belonged to the middle or lower ranks of the nobility in Burgundy. As he was a younger son, it is probable that he held very little land in his youth.

Through the reign of Philippe VI (1328 – 50) he regularly resided at the Castle of Pierre Pertheuis, which came into his hands via his first spouse, Jeanne de Toucy. He also had in his possession the tiny hamlet of Lirey, which was part of his mother’s dowry. His first wife died in 1342 without issue. Next, Charny married Jeanne de Vergy. This brought him into possession of Montfort and Savoisy. In this marriage he had two children, the heir Geoffrey and a daughter, Charlotte.

The first time he is heard of, he was leading a small troop of five squires in 1337, campaigning in Gascoigne. At this point, he was obviously a young nobleman lacking the means to set up his own military company. Later, he campaigned in Flanders and Hainault, serving under the Constable of France. In 1340 he took part in the defence of Tournai. In 1341 he then fought in the civil war in Brittany, which worked like a proxy for the renewed hostilities between England and France. Further, in 1342 he was in charge of a cavalry attack at Morlaix, which led to his capture and subsequent safe keep in Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire. Soon after, though, he was ransomed and once more back in the service of the French king, now serving as a knight. At this time he took part in raising the siege of Vannes in Brittany, now in the role of marshal.

At this point in his career (1345) he joined the crusade of Humbert II, dauphin of Viennois, the so-called campaign of Smyrna. This was an obvious disaster. Later he described crusading as a kind of quasi-martyrdom. It has been speculated that Charny was able to acquire the Shroud of Turin during this military escapade. This might explain the mixture of exotic pollen which has been found on the linen.

Finally fed up with Crusading Humbert decided on a semi-religious career. Charny, on the other hand, was soon back in the saddle. Nevertheless, he managed to miss the great battle at Crécy, but we meet him again busy defending the town of Béthune. Later, he functioned as an emissary to Edward III, who was besieging and later took Calais.

The Order of the Star

At this point, France at the loosing end was catapulted into a political crisis. This resulted in the formation of a new (and younger) royal council, on which Charny was called to serve. This came with a residence in Paris, a convenient base for his new role as both diplomat (negotiator of treatises) and the official bearer and guardian of the Oriflamme, the royal standard of France. It is at this time, we meet him trying to bribe his way into Calais in 1349 in order to take the city for the King of France. Once again, though, he was taken prisoner of war by the English and brought to London. In 135, after eighteen months, he was once again ransomed, this time by the new French king, Jean le Bon, for the sum of 12000 golden scudis.

In 1352 he was called as a prominent member of the new French chivalric order, the Company of the Star, which the king founded in 1352 and intended to outshine the Order of the Garter, instituted at the same time by the English king. It is probably around this time, the king commissioned Charny to write the series of works, which were meant to be manuals for the knights of the order. These books have secured him a prominent position in the history of Chivalry.

Also, he seems to have toyed with establishing his own personal “order” by founding a collegiate church in Livrey, manning it with five canons and commissioning a family graveyard next to it.

According to the royal decree, the Company of the Star was to meet twice a year at the in Saint-Ouen, near St. Denis. Unfortunately, the grand project of enrolling more than 500 knights met with devastating defeat. While eighty members died on the battlefield at Mouron in 1352, the project collapsed entirely after Poitiers 1356, when the king was taken prisoner by the English, and Charny died so valiantly trying to keep the Oriflamme aloof.

At first, he was buried at Poitiers. Soon after, though, he was given a re-internment in the Church of the Celestines in Paris. Destroyed during the revolution, the tomb no longer exists. This was against his strict wishes, which were to have his body primarily buried at Lirey after parts having been sent to other designated churches, thus securing a continuous prayer for his soul.

Luckless Hero or Favoured Knight?

The life and career of Charney may look rather hapless. Twice captured, and unsuccessful in retrieving Calais, he met his death in a pitched battle, which set the French back until they finally gained the upper hand after appearance of Joan of Arc in 1428. On the other hand his contemporaries obviously thought of him as a very gifted soldier. Froissart said that he “functioned like a king” when the business came to war and characterised him as “the most worthy and valiant of them all”. Finally, when reading his books on chivalry, it appears he did in fact not only “talk the talk”; he also “walked the walk”, until he finally died defending king, nation and honour with the knightly loyalty, valour and prowess, which he so eloquently outlined as the key qualities of a true knight.

SOURCES:

Autour du Saint Suaire et de la collégiale de Lirey (Aube)

By Alain Hourseau. Books on demand 2012.

A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry. By Geoffroi de Charny, Elspeth Kennedy (Translator) and Richard W. Kaeuper (Introduction). University of Pennsylvania Press 2005, pp. 28 – 29

READ ALSO:

Holy Warriors: The Religious Ideology of Chivalry

By Richard W. Kaeuper

Philadelphia, Pa: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009

ISBN 978-0-8122-4167-9.

Geoffroy de Charny (début du XIVe siècle – 1356). “Le plus prudhomme et le plus vaillant de tous les autres”

By Philippe Contamine

In: Histoire et Société: Mélanges offerts à Georges Duby/ textes réunis par les médiévistes de l’Université de Provence.Université de Provence 1992, Vol II, pp 107-121

Medieval Chivalry

By Richard Kaeuper

Series: Part of Cambridge Medieval Textbooks

Cambriudge University Press 2016

ISBN: 9780521137959