This year, the city of Goslar in Harzen celebrates the 1000-year anniversary of the birth of Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor with exhibitions and a series of lectures shedding new light on this “the most pious of kings”.

When planning the 1000-year anniversary of the birth of Henry III, the organisers nearly suffered a heart attack when the experts began to doubt the date of his birth. Was it 1016 and not 1017?

As plans had moved forward, it was nevertheless, decided to proceed. Hence we are able to visit Goslar in 2017, enjoying once again one of those huge exhibitions, the Germans are masters at curating plus the fascinating surroundings of the World Heritage Site of Rammelsberg and the ancient silver mines.

Goslar

When Henry III inherited the Holy Roman Empire after his father in 1039, Goslar was already an important royal palace. Located at the foot of Rammelsberg, where the Ottonians had (re)discovered rich silver-mines, his predecessors, Henry II (973 – 1025) and Conrad II (990 – 1039) soon developed a certain affinity for Goslar with its neighbouring forests offering rich hunting-grounds. Another advantage was the location south of the impressive royal fiscal lands, formerly belonging to the Saxon stronghold at Werla, 20 km northeast of Goslar. At first, it was no more than a hunting lodge. Soon, however, Henry II began to turn Goslar into a favoured centre of the Salian dynasty. While his son, Conrad, at first preferred Nijmegen, his grandson Henry III visited Goslar at least once every year from 1039 – 2017, reinstating Saxon Harz as the heartland of Germany. It is during this period, he was responsible for the construction of a whole new royal complex, complete with a palace, a chapel and a collegiate church (cathedral).

Though the cathedral was torn down after 1810, Goslar still holds one of the few secular buildings preserved from the 11th century, the royal palace. Although heavily restored in 1868 – 1875, it still retains some elements of the original building. But, beware, the national historical importance led the restorers to improve the building beyond recognition: the roof was raised, windows were changed and a monumental frontal staircase was placed at the centre of the façade. Inside, the national romantic painter Hermann Wislicenus painted a monumental series of frescos celebrating the imperial past of the Holy Roman Emperors. Famous is the mural, which portrays William I (1797 – 1888), which his son, the later emperor, Frederick III (1831 – 1888) behind. To each side stands young maidens representing Alsace and Lorraine (Elsass and Lothringen) and to the right stands Bismarck rendered as an architect forging the “new” 19th-century empire out of the spoliae of the past.

The Goslar of Henry III

Archaeological excavations have of course sought to get a sense of the history of the building. Originally it consisted of a long house in two storeys, measuring 54 m long and 18 m wide. Below was the guards’ room, while above a great hall with a central dais – the throne room – was to be found. From here an exit was possible to a central balcony, obviously used by the emperor when receiving the acclamation of the assembled local magnates and nobles. It is also probably that he used the balcony to watch the procession of clerics winding their way from one chapel to the next. Exactly how these processions were organised is not known; but they did constitute a central part of the royal performance of the most pious emperor, as he was want to call himself. In all likelihood, he also plied the law from his balcony; or at least had it read aloud.

The complex was fitted with separate kitchens, stables, storage facilities as well as residences for the ministerial canons and clerks as well as the entourage of the emperor. To the north was an adjoined, two-storey residential building, reserved for the emperor and his family. From here the emperor had direct access to the private chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary. This consisted of a central square building with three apses and a west-work with two towers. With the ground floor reserved for the ordinary staff, the upper chapel was the private imperial chapel. This chapel was dismantled in the beginning of the 18th century.

The later chapel of St. Ulrich (from the 12th century), which is still standing, was not so unlucky. Used as a prison from 1575, it was kept intact. Today, it holds a sarcophagus from the 14th century, which used to stand in the Cathedral. According to his own wishes, it holds the heart of Henry III. The rest of his body lies in Speyer.

From the central entrance into the imperial hall (on top of which was the platform, which the emperor had access too from the upper throne room) a hundred metre led to the west-work of the collegiate church. From his balcony, the emperor was able to watch the

The layout of the site reminds us of the Carolingian palaces in Aachen and Paderborn. As such it was one of the last palatial buildings erected in the Carolingian form. The son of Henry III, Henry IV, who was born at Goslar, was responsible for the construction of the nearby Harzburg; in the form of the new-fangled medieval castles, this signalled a new era and the more rebellious

The Exhibition 2017

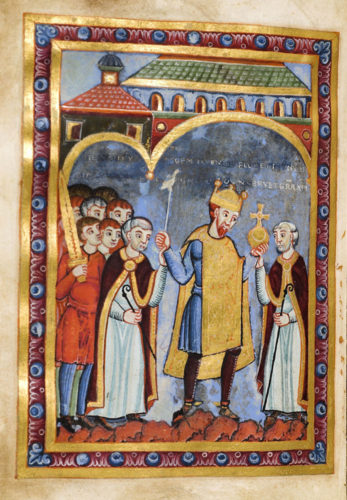

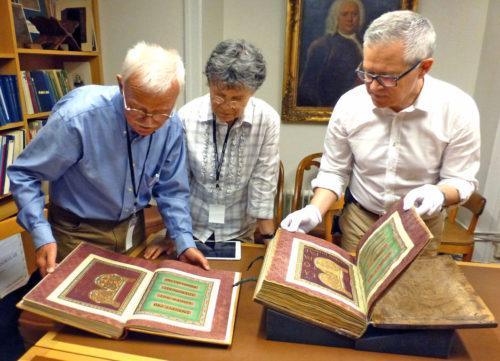

Soon after his enthronement, Henry commissioned a number of elaborate manuscripts from the scriptorium at Echternach. One of these, the Codex Caesarius Upsaliensis (former Goslariensis), was intended as a gift to the newly founded college church of St. Simon and St. Jude, which he might have intended as a hothouse for future prelates in the churches of his empire. The Codex was in all likelihood stolen during the 30th year’s war in the 17th century and has for the last 400 years been kept in the library in Uppsala in Sweden. Now, for the first time in centuries, the elaborate codex comes home.

The exhibition is planned to open on in September with a special lecture given by Dr Tillmann Lohse from the Humboldt University in Berlin. This is the first of a number of lectures, which will obviously be published at a later time. The exhibition, with additional events, is planned by the Museumsverein Goslar.

FEATURED PHOTO:

Codex Caesarius Upsaliensis (former Goslariensis), fol 10– 11. Photo: University of Uppsala.

READ MORE: