The title of the Papal Encyclical, Laudato Si, is the refrain of the Canticle of Creation by Francis of Assisi. But what did the saint really mean by using this phrase?

St. Francis is known for many things. In fact, he has often been named as “a man of all times”, ready for both use and abuse by the generations, which followed in the footsteps of this little, big man. The latest installment in this unfolding saga is perhaps the recent use of the refrain from his Canticle of Creation as the title of the most recent Papal Encyclical, Laudato Si.

Some facts are, nevertheless, univocal: He was a beloved instigator of a new kind of Christian Re-enactment of the message of the Gospels, which spread as a global firebrand both before his death and in the decades and centuries after. Today his message reverberates not only in the minds of the millions, who go on a pilgrimage to Assisi each year. It resonates equally among Christians from all over the world, whether Catholics or not.

The essence of this message was his experience of being called to both ‘walk the walk, and talk the talk’ in a very early Christian Apostolic sense. To be yoked to Christ meant in his view to follow in the footsteps of the disciples, as recounted by Matthew 10:9-10 (or Luke 9:3): “Do not acquire gold, or silver, or copper for your money belts, or a bag for your journey, or even two tunics, or sandals, or a staff; for the worker is worthy of his support.” Their objective was of course to spread the good Word, the Gospel. [1]

The point is St. Francis was called to live his life in the world and not outside it as the Ascetic mystics and later monks and nuns did. In this sense he was a true renovator (at the same time both a traditionalist and an innovator).

St. Francis – A Nature Mystic

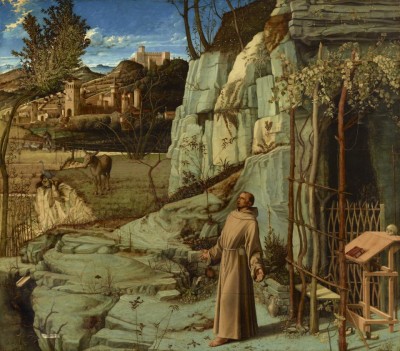

But how do you both live in this world and renounce its less palatable – worldly – life-forms? One way, of course, was to develop a new organic way of thinking about the world. The call was to partake in the world, less than denounce it or plainly use it. Out of this grew a particular new form of mysticism, which found its most prominent expression in the Christmas-miracle in Greccio, where St. Francis set the scene by building one of the first Nativity scenes, complete with the adoring animals – and ass and an oxen. Having set the scene in a grotto in this remote part of Lazio, the Baby Jesus naturally came to life amidst the adoring congregation of peasants and mute creatures. In fact, the Lives of the saints are resplendent with vignettes, telling how the saint basked joyously in the midst of Creation, in the end reaching a perfect union through the first recorded instance of stigmatization.

The Canticle of Creation

It is generally accepted that the precious song of St. Francis, the Canticle of Creation, was a late poetic rendering of this way of thinking about the world. It is generally agreed that the first 25 strophes came into being in the winter of 1224 – 25, that the strophes of 26 -30 were composed somewhat later and that the final strophes of ‘Sister Death’ were added a few days before his death.

It is generally accepted that the precious song of St. Francis, the Canticle of Creation, was a late poetic rendering of this way of thinking about the world. It is generally agreed that the first 25 strophes came into being in the winter of 1224 – 25, that the strophes of 26 -30 were composed somewhat later and that the final strophes of ‘Sister Death’ were added a few days before his death.

It is here we find the refrain, from which the: “Laudato sie, mi Signore”, from which the title of the poem and the encyclical has been taken. The question however has for a long time been whether to understand it as an acclamation or an invocation? This question hangs on how to understand the small word ‘per’ which crops into the 10th strophe (Laudato si, mi Signore, per sora Luna e le Stelle).

In fact, there exists a controversy about this word, which stems all the way back to the early “understanding” of the saint and his overall message.

The word ‘per’ may be understood as an Italian rendering as the ‘Latin’ propter = for. (Be praised, my Lord, for Sister Moo and the Stars), which means that St. Francis wished to call us to praise the creation for its qualities. This is called the ‘causal’ interpretation.

Another understanding, however, sees the ‘per’ as denoting the French ‘par’; which means the lines should be translated as “Be praised, my Lord, by Sister Moon and the Stars”. This would entail that Creation, itself, should be seen as an active agent.

There is no doubt, that Thomas de Celano and Bonaventura [1], who wrote the official Vitae of the Saint, understood his poem in this way: as an invocation to Creation to take part in the constant praising of the Lord. Just as the birds were urged to praise the Lord in the famous vignette painted by Giotto, so was the canticle to be sung as an exhortation to the full Creation to align in a prayerful pose. Another argument was that the known models for the Canticle – Psalm 148 and the Canticle of the Three Young Men – carried this understanding. These were liturgical texts, which were undoubtedly part of the daily and weekly liturgies of the first Franciscans and which carried this ancient and venerated idea: that Creation was to be understood as a mechanically aligned chorus. To be part of this chorus, was the same as to sing and be in unison with the rest of creation (but not to experience a possible mystic unification with God).

However, the “unofficial” understanding of the Canticle and the life-work of the saint differed profoundly with this interpretation. It is well-known that the Early Franciscans laboured intensely after the death of the Saint to present a sanitized version of his life and teachings. It is also well-known that only fragments of the unauthorised version were kept for prosperity. Looking at one of these texts: the detailed and informative Legend, written by some of his closest friends and companions. According to this (LP 43) “Francis received a vision in the night, which informed him that he should be “glad and joyful in the midst of your infirmities and tribulations: as of now live in peace as if you were already sharing my kingdom”. Upon this happy thought, the story tells us, the Saint began to write his Canticle concerning his creatures, which “minister to our needs every day; without them we could not live; and through them the human race greatly offends the creator. Every day we fail to appreciate so great a blessing by not praising as we should the creator and Dispenser of all these gifts”. And he sat down, concentrated a minute, and then cried out…”[2]

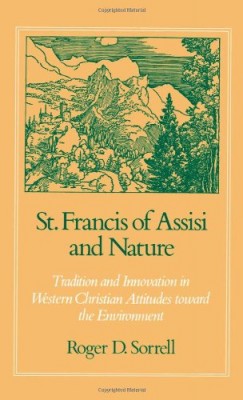

This – more causal – understanding of the poem is also substantiated by the grammar used by the saint (a point made unequivocally by Sorrel). ‘Laudato Si’ is in passive imperative and not in a normal imperative, which would have been the easiest way to invoke Creation to partake in the earthly chorus.

According to Sorrell there is no doubt: St. Francis invoked humankind to praise and give thanks for God’s creatures (his Creation). In his Canticle, the creatures were specifically glorified as special gifts of God, useful, beautiful, merciful etc. This is also, writes Sorrell, the reason why Francis in this instance wrote in his native language. The reason was to popularize his invocation by spreading it amongst his fellow townspeople and peasants – exhorting them to take part in a human praise of creation, to which people were organically and not just mechanically linked. His was – perhaps – a slightly pantheistic view, which later theologians emphatically tried to erase. However, apart from silencing the Saint, this had the grave side-effect of placing humans

Laudato Si in the 21st century

It is apparent from the very first paragraphs in the papal encyclical, which is presented today, that it is precisely NOT this organic understanding of humans’ and their relationship to God and his Creation, which has been laid to ground for what has already been termed the Pope’s “Eco-Encyclical”. In this the Pope (and his minions) writes that “Saint Francis of Assisi” reminds us that our common home, the Earth, is like a sister with whom we share our life and a beautiful mother, who opens her arms to embrace us. It is this “sister”, which now “cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her”. In short: there is strife in the earthly sanctuary. This is emphasized by the translation of the central quotation from St. Francis, which goes like this “Praise be to you, my lord, through our Sister, Mother Earth, who sustains and governs us, and who produces various fruit with coloured flowers and herbs.”

In this version of St. Francis, harmony will, it seems, be restored, when we step ascetically aside or backwards, repenting our sins while at the same time joining the heavenly chorus of the Creation in singing God’s praise together with the Angels. In short: align with Mother Earth (and Mother Church as well as the Queen of all creation), while tending to Her as we do to our garden. It is in the view of this we must read the final remarks in the introduction to the Encyclical, where the Pope writes: “All of us can cooperate as instruments of God for the care of creation, each according to his or her own culture, experience, involvements and talents.” (Introduction § 14)

Conclusion

We may think that this has no specific relevance. Here is a Pope, who does his best to get humanity to concern itself and take action in view of the manifest increasing numbers of hurricanes, droughts, animal extinctions and blatant destructive acts of the Blue Planet, which the Climate change is the most prominent symbol (and direct cause) of. As such the Encyclical is already stirring a magnitude of hornet’s nests. It is no minor thing, when a Pope tries to rally his troops, 1.2 billion people.

But it does matter! This becomes apparent when reading chapter six, which is about “Ecological Education and Spirituality”. Here we are called to curtail our compulsive consumerism and turn our back on our consumerist lifestyle; instead we are urged to reach out to “the other”. In order to bring this about the Church is urged to engage in widespread “environmental education” aimed at creating an “ecological citizenship” and the basis for an “ecological conversion” towards a communitarian (Trinitarian) understanding of the world. All this is naturally explained with proper allusions to St. Thomas Aquinas.

There is no doubt that all this is very beautiful and uplifting for Catholics. It may even lead some politicians and businessmen towards a much needed repentance and conversion. But Franciscan, it is not. Rather, there is decided whiff of the Jesuit in the air…

Of course, the question then remains, what St. Francis might have suggested, had he lived in our time? Following Sorrell, we may perhaps speculate that he would have urged us to simply slow down and take our time to really enjoy the wilderness and creatures large and small around us with gratitude and in prayerful contemplation. In short, stop being so busy, busy, busy…perhaps that might even be the best way of saving our Sister, the Earth!

Written in fond remembrance of Brother Clark Berge and his brothers and sisters, who came to Copenhagen in 2009 during Cop 15 and with whom I spent some peaceful hours in St. Alban’s.

Karen Schousboe

NOTES:

[1] Thomas of Celano: Life of St. Francis. Quoted from: Francis of Assisi. Early Documents, Ed. by Regis J. Armstrong. New York City Press 1999, Vol I.

[2] Legend of Perugia § 43 Quoted from: Francis of Assisi. Early Documents, Ed. by Regis J. Armstrong. New York City Press 2000, Vol II: p145

SOURCE:

St. Francis of Assisi and Nature. Tradition and Innovation in Western Christian Attitudes toward the Environment

St. Francis of Assisi and Nature. Tradition and Innovation in Western Christian Attitudes toward the Environment

By Roger D. Sorrell

Oxford University Press (1989) 2009

Lettera Enciclica Laudato si’ sulla cura della casa comune

Published in Arabic, French, English, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish and German

HEAR MORE:

It stands to reason that YouTube presents us with a virtual cornucopia of videos with Franciscans performing the Canticle of Creation. Here is a favorite, tacky yet lovely: