Mikulčice was a Slavic settlement from the 9th century. With the remains of fortifications, a palace, twelve churches, a huge acropolis and extensive suburbs, it continues to yield new insights into the early history of Moravia

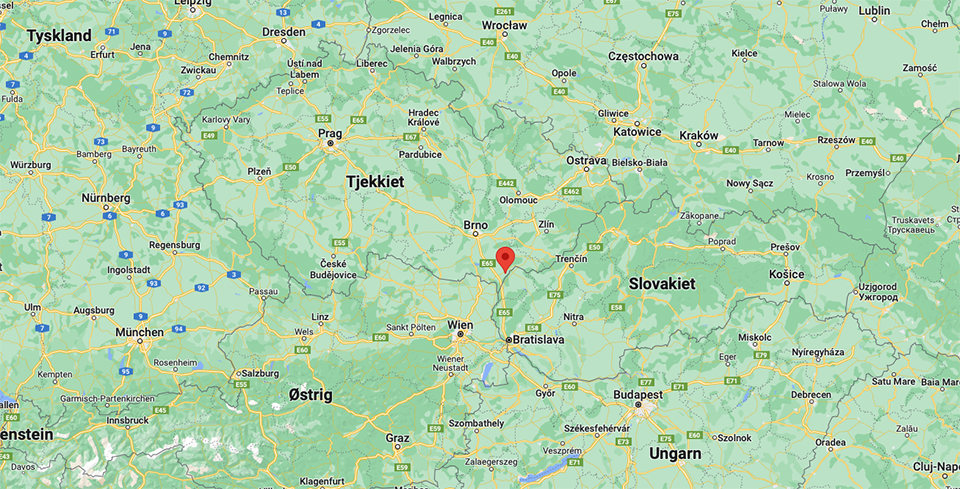

Moravia is one of the critical gateways in Europe. With the Bohemian Massif to the northwest and the Carpathians to the southeast, the river basin of Morava with its tributaries is one of the few places where physical movement back and forth from the Danubian to the Polish lowlands was possible. Through the lowland flows the river Morava, a tributary to the Danube, which runs from the north to the south. As such, the river valley has functioned as one of the important gateways for migrating wildlife meandering through eastern and central Europa searching for new grazing lands‚ north or south as the climate or mood dictated. Later, from the 16th century BC, the route through Moravia became a central part of the amber route moving the “Northern Gold” from the shores of the Nordic and the Baltic seas to kings and other magnates operating along the circumference of the Mediterranean Sea.

During the communist reign, the river was heavily polluted with industrial waste, and even today, the river is a sorry sight; long stretches are regulated and devoid of life. However, near Mikulčice and the adjoining Skařiny Nature Reserve, it is possible to get a sense of the landscape in its former glory. Also, Mikulčice is surrounded by a natural park, covering eighty hectares peopled by beavers, storks, kingfishers and other wetland birds. A couple of km to the northeast, a major renovation project is currently ongoing, while other projects aim to set the floodplain ecosystem partially free to allow for a more natural overflow. This effort is currently being stepped up to re-establish the retention capacity of the flood banks. In 1997, a devastating flood killed 45 people and caused the evacuation of numerous villages, but even minor floods are a constant threat. Thus, moving backwards in time, we have to imagine a wet and marshy landscape surrounding the hillfort at Mikulčice.

In the 6th and 7th centuries, Slavic tribes – Sklavinoi – arrived on the coattails of the Avars, a nomadic Central-Asian people of mixed heritage who settled in the region. Later, in the 9th century, the first Moravian “kingdom” came into being. With the ruins of the late Avar Khaganate in the backyard, the Moravians were in a constant war with the German Carolingians – who considered the territory a march or borderland. Moravia is first mentioned in the written sources in AD 82 when envoys turned up in Frankfurt. Later, Moravia was overrun by the invading Magyars in 907. After the Ottonians defeated these nomads in AD 955 at Lechfeld, Moravia was overtaken by first the Bohemians and later the Polish rulers. However, after AD 1019, the land of Moravia came under the rule of the Bohemian princes.

Greater Moravia, Mojmirid Moravia, or just Moravia?

At the centre of this story resides the mythic figure of Mojmir, who – according to the History of the Bishops of Passau – was baptised with his retinue and people sometime around AD 831. The event was organised and carried out by the Bishop Reginhar of Passau. Likely, the story represents a piece of the traditional mythmaking common among missionary bishoprics trying to claim the rights to the missionary fields among the heathens. Pertinent in this connection is the later story of how Mojmir’s nephew Ratislav, King Louis the German’s vassal, successfully fought the East Frankish king in AD 855. At this point, Ratislav turned his allegiance towards the Byzantines, allowing the two “national” saints, Cyril and Methodius, to set up a competing Christian church organisation in Moravia. According to their vitae, they used the Slavonic language and created the Cyrillic script to evangelise the people living in Bohemia, Moravia and further south. Subsequently contested by (among others) the Bishop of Salzburg, the papal recognition of the Slavic Church and its distinct liturgy was nevertheless secured in the aftermath.

Later, Ratislav joined up with Louis the German’s son, Carloman, rebelling against his father. After Carloman reunited with his father and fought Ratislav, the German annals and chronicles present us with a typical back-and-forth history. Finally, in AD 868, Ratislav’s nephew, Svatopluk, captured the old king and sent him in bonds to Regensburg, where he was blinded and kept prisoner to his death in AD 870. Now Svatopluk ruled Moravia and wider dependencies. In AD 890, Svatopluk was even called a king in some sources. However, a few years later, local infighting appears to have caused the fledgeling “kingdom” to collapse. When the name “Megale Moravia” appeared in a Byzantine chronicle in AD 913–59, it referred to a glorious past of a region long subsumed under the rule of its neighbours – Bavaria, Hungary, and finally Bohemia.

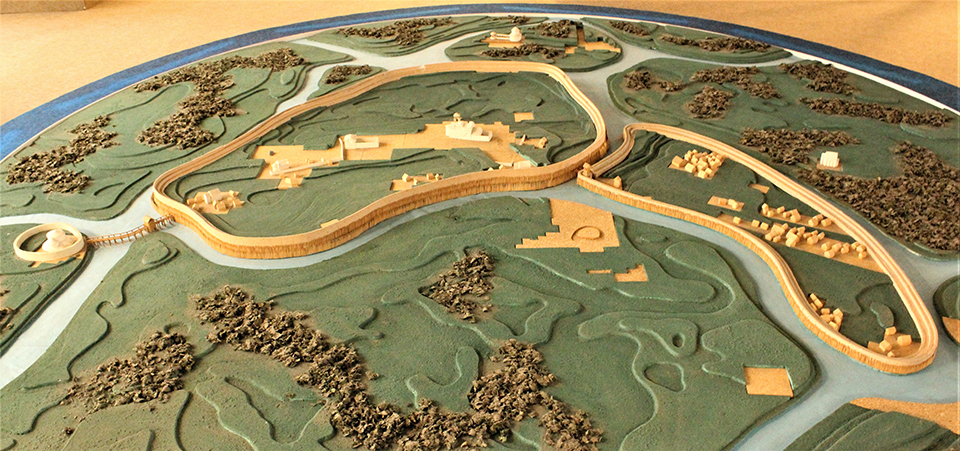

The Fortifications at Mikulčice

In the mid-20th century, archaeologists began excavating the Slavic hillfort at Mikulčice, built in the middle of the marshes on a hill consisting of sand dunes. Since then, excavations have revealed a considerable amount of information about the fortified site and countless objects, from boats to golden spurs. Complete with a fortified compound with an excavated palace, several churches and a vast burial ground with more than 2500 graves, and large suburbs with workshops, the site continues to yield new information about the lives of the Moravian elite in the 9th and 10th centuries. Located on an elevation in the river marshes, the fortified centre was likely supplied by boats, while the hinterland offered a living for dependent peasants, woodsmen and craftsmen. Within the wider settlement, ten to twelve church buildings have also been excavated, with more waiting to be studied. Among these, the so-called basilica remains the ruin of the largest ninth-century church in Moravia. Likely, it was episcopal. Some of these churches have held what is believed to be dynastic burials. Numerous excavated objects are embellished with Christian motifs indicating a vibrant clerical element in the population.

Today, Mikulčice is considered one of several “central places” where the Moravian elite had their power base. Perhaps, it was even the royal centre of Mojmir, Ratislav and Svatopluk? This is suggested by the inordinate number of churches excavated on site. At least, during the 9th and 10th centuries, kings, local magnates or junior princes appear to have lived as local magnates in Moravia, perhaps residing at Mikulčice, located on a hill of dunes in the middle of the marshy surroundings of the river Morava.

Greater Moravia and Mikulčice

However, the excavations at Mikulčice were never just innocent inquiries into a particular geo-political linkage between the north and the south and its role as a vibrant inland emporium and fortification in the borderland between east and west. Early on, Greater Moravia came to represent one of the essential emblematic signposts of Slavic independence in the history of Europe after 1919, when the Czech and the Slovak representations brought this idea to the political table at Versailles. According to traditional Czech historians, Moravia was not just one of many “marches” or borderlands subservient to their large German neighbour. Squeezed in between, on the one hand, the Avar Khaganate and the later Magyars, and on the other hand, the Carolingian, Ottonian and Bohemian overlords, the history of “Greater Moravia” – if it ever existed outside the phantasies of nationalist historians – gained ground in the 20th century.

One reason was the Soviets and their interest in discovering the roots of Slavic supremacy. In this history, Mikulčice came to play an inordinate role. Thus, the Russians supported the large-scale enterprise when the first excavations took place in the mid-fifties. Here was physical evidence supporting the Marxist history of the very early feudal mode of production, which might underwrite the Soviet idea of Russia as the mother of the overturn of the later capitalist revolution. Later, however, when the Soviet Union collapsed, funding for the excavations soon dried out. Instead, Czech and Slovakian people began to lobby for the status as UNESCO World Heritage – thus propping up the nationalist myths – while archaeologists, historians and art historians began to sift through the enormous masses of excavated finds.

Today, the status of Great Moravia as a distinct polity is considered less important than understanding the character and inner workings of this early medieval border region. In this work, Mikulčice, as an early medieval central place, continues to provide new insights and yield new information. Not least, new scientific methods developed in the last decades provide us with a better understanding of the situation of the place. Main research topics are the palaeo-ecology of the valley floodplain in the Early Middle Ages, the economic basis of the hinterland, the structure and history of the fortifications, the social structure of the Great Moravian population, and the question of the role of Christianisation and early church organisation. Some are carried out by researchers at the National Museum in Prague others at research centres in Brno and at Mikulčice.

Studies recently published cover pig-breeding, bioarchaeological finds, material culture, jewellery, and the physical remains of people.

Pig-Breeding at Mikulčice

One question has been how the large population living at Mikulčice – a semi-urbanised fortified central place – was fed from the hinterland. One of the prominent finds in the settlements were bones from animals, of which the pig appears to have played a relatively significant role. The questions have been, though, where these pigs were sourced, whether they lived in the wild or were they kept penned-up in pigsties? And further, how were they fed and fattened, at what age were they slaughtered and what social, if any importance, were attached to the animals?

First, the importance of the pigs may be gathered from the relative number of specimens. With pigs accounting for 53%, cattle at 18%, sheep and goats at 19% and horses at a miserly 0.2%, pork appears to have been a favourite source of proteins. Game played only a tiny part. Secondly, it should be noted that pigs were eaten both in the palace and the more humble abodes in the suburbs. However, as might have been presumed, the elite did not eat their pigs at an earlier age than people in the suburbs. About 50% of their pigs at court were slaughtered one to two years old, while 75% of those eaten in the working area were young animals. However, the animals eaten by the elite were more often male. Unfortunately, the article does not indicate where the eight wild boars mentioned were served. The number of older males consumed in the palace may give us a hint. Osteological studies have also shown that the animals were predominantly fed extensively on the grass meadows and open forests surrounding the site.

Bioarchaeological studies

In the same manner, new studies of the archaeo-botanic finds from more than fifty years have yielded valuable insight into the foods and drinks consumes at Mikulčice. Since the surroundings are generally wet, the finds are extensive. First, wheat, rye, barley, oats, and millet have been found. To this should be added lentils and peas, but also bitter vetch, Celtic beans and grass peas. Furthermore, stones from peaches, grapes, apples, pears, plums, and walnuts were discovered, as were such vegetables as cucumbers. Finally, oil plants were present such as hemp, flax and puppy. All-in-all, 27 different crops would have been cultivated. However, the menu would also have included sweet cherries, blackthorn, raspberry, dewberries, cornelian cherries, wild strawberries and hazel nuts. Some of these fruits might have been used for medicinal purposes, such as hawthorn, elder, and rowan. However, hawthorn supplies a tangy and interesting citric taste to any pot, as does elder berries and rowan. We do not know.

All these delicacies were found both at the fortified centre and the outer bailey, together with an abundance of wheat and millet. However, in the outlying areas, a somewhat courser diet has been registered with rye dominating with lentils and peas, while bread wheat and millet were less common. Regarding the quality of the seeds, the scientists did not discover a pattern of “better seeds” being present at the centre as opposed to the outlying villages. “In summary, we can say that the measured seeds formed a single unit, with no significant differences between individual areas within the Mikulčice- Kopčany agglomeration observed”, writes the authors (Látkova 2023). However, the wheat consumed at the fortress appears to have grown nearby in more extensively (less manured) fields in the water-inundated landscape between the rivers. Contrary to this, the grain consumed in the hinterland appears to stem from better-manured fields, indicating a self-sufficient agrarian regime organised around and infield- outfield system. Perhaps, the agricultural regime in the six km wide flood plain was organised as an open-field system? As of now, though, the authors are careful not to conclude. Further research is needed to explore the possibilities

The Jewellery

One of the more fascinating collections of finds at Mikulčice is the jewellery recovered from the elite burials inside and outside the churches. Although often classified as Byzantine, it has later been termed Veligrad-Jewelry, and the artistic legacy and chronology seem to be complicated to assess.

A new book – building on years of hard work – aims to tackle these questions. Especially chronology and dates are at the fore. However, multiple questions remain concerning the typology of both earrings and the characteristic gombiky, the spherical and hollow buttons fitted with a loop and made of gold or gilded copper. Some were even fitted with small inside metal balls, literally turning them into small bells giving off a clinking and clanking sound.

The gombiky have been found in graves from all of Moravia but also in neighbouring regions in Hungary and the Balkans. However, from the significant material excavated at Mikulčice (440 and counting), they were predominantly found in the elite graves excavated inside, constituting 9% of all assemblages. Also, they all differ in terms of decoration. Therefore, the archaeologists believe the gombiky were made to order by the elite and not for the “open” market.

Definitely, some of the gombiky were used as buttons. Often believed to be inspired by the Asian fashion of bottoming-up caftans, art historians, however, now believe that the gombiky were primarily part of the Byzantine fashion of sowing pendilia to clothes, headdresses or as hangers embellishing so-called clavi sown on to Early Medieval tunics. Such Byzantine pendants were – like the Moravian – crafted with soldered filigree and granulation. However, the prevalent vegetal geometrised ornamentation is thought to derive from Iran and Near-Eastern Mediterranean Christian ornamentation. Approximately 40 gombíky from Mikulčice sport Christian motifs such as crosses, fishes, birds and palms.

The gombiky have been found in male as well as female graves. Earrings, on the other hand, were definitely gender specific. As with the gombiky, they may have hung from the earlobes, but just as often, they may have been attached to the headdresses. These earrings were made with the same technique with the artist soldering granules and wires onto the skeleton or creating them with beads covered in granules. Some might be crescent-shaped, while others looked like gombiky. Generally, the Byzantine influence seems to have provided artistic inspiration, but in terms of hooked spurs and belts, the people at Mikulčice probably looked elsewhere. Her inspiration may have derived from their Avar and later Frankish overlords.

The People

Recently, a study based on a strontium analysis of 123 human molars was published. The aim was to get a sense of the geographical catchment area of the people who lived at Mikulčice, among these 32 elite males, 38 elite females, 25 non-elite males and 27 non-elite females. The elite character was established through the location of the grave (inside/outside the church) and the character of the grave goods: gold, textiles, tableware, lavish belt fittings, swords, spears, spurs and jewellery. Of the 123 persons, at least 21 were identified as non-local – 13 to 19%. Identifying where these people came from is not easy. However, the scientists suggest three areas which might have been feeding Mikulčice, one 60 km to the northwest, another 45 km to the northeast and finally, one location 90 km to the north. Further, the hypothesis of Mikulčice as a patrilocal society had to be disregarded. The material was not able to provide confirmation thereof. It appears that the elite at Mikulčice was not partners in the Carolingian or Byzantine matrimonial networks.

Also, Moravian society was most likely made up of local people, writes the scientists. Thus, based on this evidence, Mikulčice was a critical regional seat of power in Moravia, and, definitely, it was a Christian hotspot in the early missionary period. However, the people living and buried there were likely born and bred locally or regionally. These results may be compared to the finds from Birka and Sigtuna in Viking Sweden, where more than half of the population arrived from afar. As both these sites must be characterised as early urbanised, the question concerning the character of Mikulčice as such must be raised. Thus, the authors do not see evidence for a corresponding early urbanisation, and neither do they believe that Mikulčice would have been entangled in an economy based on slavery (as has been suggested elsewhere). However, on this point, they agree that a study of the more peripheral cemeteries are needed to come to a solid conclusion.

To conclude, the painstaking studies of the vast assemblies of finds from the excavations at Mikulčice continue to yield new information about the myths and facts about the history of “Megale Moravia“.

SOURCES:

Environmental Archaeology. The Journal of Human Palaeoecology

Pig-Breeding Management in the Early Medieval Stronghold at Mikulčice (Eighth–Ninth Centuries, Czech Republic)

By L. Kovačiková, S. Drtikolová Kaupová, L. Poláček, P. Velemínský, P. Limburský & J. Brůžek

In: Environmental Archaeology (2022) Vol 27 No 3, pp 277-291

Bioarchaeological Characteristics of the Wheat (Triticum aestivum) Consumed at Different Parts of the Early Medieval Settlement Agglomeration of Mikulčice-Kopčany (9th–10th Century AD, Czech Republic)

By Michaela Látková, Roman Skála & Sylva Drtikolová Kaupová

In: Environmental Archaeology, DOI: 10.1080/14614103.2023.2176613

Prunkvoller Frauenschmuck während des langen 9. Jahrhunderts im Mährerreich: Typologie, Chronologie und historische Bedeutung

By Hana Chorvátová

Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 20. mar. 2023 – 309 sider

Residential mobility in Great Moravia: strontium isotope analysis of a population sample from the early medieval site of Mikulčice-Valy (ninth–tenth centuries)

By Zdeněk Vytlačil, Sylva Drtikolová Kaupová, Michaela Jílková, and Lumír Poláček,

Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2021) 13: 8

The articles reflect a series of monographs or guides published by Archeologický ústav AV ČR on the introduction of the results of the archaeological excavations in Mikulčice to the general public.

READ ALSO

Great Moravian Elites From Mikulčice

By Lumír Poláček et al.

Co-authors in alphabetical order: Peter Baxa, Šárka Bejdová, Lucie Bigoni, Helena Březinová,

Petra Brukner Havelková, Jaroslav Brůžek, Hana Brzobohatá, Sylva Drtikolová Kaupová, Luděk Galuška, Matej Harvát, Marek Hladík, Michal Hlavica, Jiří Hošek, Alexandra Ibrová, David Kalhous, Jiří Košta, Pavel Kouřil, Lenka Kovačiková, Šárka Krupičková, Jakub Langr, Michaela Látková, Jiří Macháček, Marian Mazuch, Estelle Ottenwelter, Rudolf Procházka, Dana Rohanová, Hedvika Sedláčková, Vladimír Sládek, Petra Stránská, Šimon Ungerman, Lucie Valášková, Jana Velemínská, Petr Velemínský, Eliška Zazvonilová

Czech Academy of Sciences, Institute of Archaeology, Brno

Brno 2020

Mikulčice and Its Hinterland: An Archaeological Model for Medieval Settlement Patterns on the Middle Course of the Morava River (7th to Mid-13th Centuries),

By Marek Hladík

Series: East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 vol 61)

Leiden: Brill, 2020.

doi:10.1086/722068

The Fall of Great Moravia. Who Was Buried in Grave H153 at Pohansko near Břeclav?

Ed. by: Jiri Machacek and Martin Wihoda

Series: East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450-1450, Volume: 54

Brill 2019

READ MORE:

In 12014, a new research centre was founded at Mikulčice-Trapíkov at the periphery of the archaeological site. The new base provides ideal conditions for interdisciplinary archaeological research into Mikulčice, Great Moravia and the Central European Early Middle Ages. The Research Centre is affiliated with The Institute of Archaeology in Brno at the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague.

Arguably, it is considered one of the most modern archaeological research facilities in the Czech Republic. Here, archaeological finds from Mikulčice and from other early medieval Moravian sites are conserved, restored, documented, stored in study depositories and professionally evaluated.

The aim of the activities at the centre is to study Mikulčice and Greater Moravia in the widest possible sense. The entire interdisciplinary archaeological research is supposed to answer the basic – and so far not satisfactorily answered – question of the role of Mikulčice and Greater Moravia in the history of 9th-century Central and Eastern Europe. By maintaining a close relationship with its archaeological locality, the workplace ensures there is the opportunity to clarify specific research questions directly in situ.Prominent research topics include the beginnings of Christianity and statehood in this territory, the social and economic problems of early mediaeval settlements and the reconstruction of the natural environment of Great Moravian island castles. The historical and research importance of the Mikulčice-Valy locality make it an example of an early mediaeval power centre par excellence. In this context, the Mikulčice archaeological base has the potential to be the perfect centre for international research into Great Moravia.

The local finds, together with the relevant technical equipment, are made available to the staff of the Institute of Archaeology as well as other researchers. Public information systems dealing with the archaeology of the Moravian early Middle Ages will be created that will use the database applications of the Mikulčice excavations. The publishing activities of this workplace have resulted in several publications − mostly in English and German.

VISIT: