In the 21st century, we are looking towards a time when the Middle Ages return, claims a group of political commentators

In recent years, it has become “modern” to highlight the Middle Ages as a colourful and bright period, where people – despite all sorts of misfortunes – made things happen. When we remember the Medieval times, the focus is often on urban development, new art forms, new agricultural practices and crops, the cultivation of barren land, church construction, and much more. “The Colourful Middle Ages” was the title of an exhibition at the National Museum in Copenhagen some years ago. An English echo was released last year titled “The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe.”

In a way, it makes sense. The Middle Ages were filled with colours for those who could afford it – the monasteries that created illuminated manuscripts, the churches with their stained glass and frescoes, and the nobility in their fine silk and brocade attire.

However, underneath, the Middle Ages was a rather dark and dismal affair. Ordinary people, as most were, were hardly interested in the colour of their clothes but rather if the tunic covered their backs and kept out the cold.

The First Millenium

According to some contemporary observers, we should take note of this, the point being how the history of the Middle Ages precisely illustrates what happens when societies break down. At no time was this societal breakdown more pronounced than at the turn of the first Millenium – i.e., around 900 – 1100.

The story here briefly outlines how the Carolingian Empire (751 – 888) began to dissolve after 840, and commonly explained in several ways:

* The heirs of Charlemagne – his grandchildren – fought each other to the death, resulting, among other things, in the famous Battle of Fontenoy in 841, which was vividly described at the time as one of the bloodiest and most terrible because father and son fought on opposite sides and against each other.

* Another explanation, however, is that the weather turned warmer, making it possible to develop or adopt new technologies and cultivate more land, contributing to a shift from intensive to extensive land cultivation. Although the yield per hectare was smaller, doubling the acreage under the plough and spreading two- and three-field cultivation systems meant a greater yield. This increasing productivity led to population growth establishing a more robust local workforce that might be exploited in new ways.

* Hence, the benefits of serving in the king’s military, participating in conquests against neighbours and extracting tribute became less attractive. In contrast, building one’s castle and forcing the local peasants to cultivate the land was more economically advantageous. In general, this is referred to by the concept of “feudalism“.

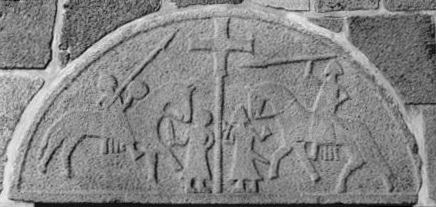

The result of this seismic shift was a general weakening in the 10th century of the states in the core areas of Europe (present-day France, Germany, and Northern Italy) in favour of the emergence of more or less independent lords who exploited their subjects – i.e., peasants as well as other common folks. Of course, kings and emperors were operating in this fragmented medieval landscape. Ultimately, though, their power depended on their charismatic ability to organize a defence against the marauding bands and pirates operating from the European periphery – the Vikings, the Slavs, and the Hungarians. It was certainly not easy, as everyone looked out for themselves. Hence, the the historiography of the time was filled with descriptions of warring and attrition mingled with grandiose words about oaths sworn, promises broken, and raw, unadulterated violence.

Reading the chronicles of past times in French, German, English, and Irish vividly describes this fragmented world filled with violence and unrest. In Flodoard of Reims, for example, we read in the introduction to the year 919 that “this year there was no wine in the region around Reims” and that “the Norsemen plundered, destroyed, and annihilated everything and everyone in Cournuaille, located on the coast of Brittany. People from Brittany were abducted and sold, while those who escaped were driven out. Meanwhile, the Hungarians plundered Italy and parts of Francia, that is Lothair’s kingdom.” That same year, Flodoard reports how the French king’s men renounced their allegiance and loyalty to him because the king would not expel one of his favourites. Overall, Flodoard’s chronicle is filled with accounts of murder, arson, rape, slavery, sieges, battles, and just general death, destruction, and misfortune. As if that weren’t enough, Flodoard’s chronicle also contains a steady stream of accounts of hailstorms, earthquakes, and other natural disasters.

Moreover, following this fragmentation of the Carolingian power base, the kings’ monopoly on minting and collecting tolls was eroded, so even though the economy generally grew, wealth spread to the periphery and enabled the countless Wagner-like groups that terrorized their surroundings.

It is characteristic that even though the Catholic Church launched two attempts to control the anarchy – a fight against the secularization of the church through reforms of the spiritual life paired with the establishment of the peace movements (Pax et treuga Dei), it was a long and challenging process. The English King’s murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket in 1170 in Canterbury was one of the more spectacular examples of how the church generally struggled to shore up its people, its wealth and its tempering influence.

Out of this chaos, some stronger states gradually emerged on the periphery. One of these was the Holy Roman Empire, which still had the opportunity to exact tributes from their neighbours – the Slavs along the Baltic, the Poles, and the Central Europeans, whom they gradually managed to subdue. Another was the Danish North Sea power, which succeeded in gathering Denmark, Norway, parts of Sweden and England under one roof. We know it as Cnut the Great’s North Atlantic empire. The Vikings in Kyiv (Rus), who created a trading nation that stretched from the Black Sea to Novgorod, were a third political power base. Although France as a kingdom gradually got back on its feet, it was not until after the end of the Hundred Years’ War in 1453 that the France we know today emerged, just as it was only in 1492 that Spain became a unified nation. Italy only succeeded in unifying in the 1800s. Behind this shoring up of the future nation-states lay economic growth vested in the plundering raids of the Crusades. Later, wealth accrued from the colonization of Africa and, later, the Americas and the Far East.

The Neomedieval Era.

Increasingly, modern observers point to the events at the turn of the first millennium to understand the time in which we live. They, therefore, speak of us living in the Neomedieval Era.

Politically, the strong nation-state is rapidly declining, while large global economic empires are increasingly setting the agenda. An example of this is Elon Musk with his satellites, which are crucial for Ukraine’s warfare. Another example is Facebook, which effectively still allows a frightening spread of conflicting fake news – simply because it is advantageous for the “algorithm.” Politicians trying to control the global enterprises of Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, and Musk appear clueless.

The decline of the nation-state has already triggered severe political crises in many countries, and the problems with this weakening will continue as trust in the democracy and legitimacy of politicians erode. The relatively high degree of social solidarity that dominates in the welfare states has splintered while competing sets of identities are on the rise (wokism).

Economically, neomedieval states experience slow and unbalanced growth, primarily benefiting a small minority, the super-rich. Neomedieval economies also exhibit disparate growth rates, entrenched inequalities, and growing problems with illegal mafia-like economies (bitcoins). Climate change and nature depletion challenges should be added to these economic imbalances. We may no longer find a solution by robbing and raiding people in far and uncharted waters on the other side of the globe. We are left with the option of exacting taxes from our neighbours.

The nature of security threats has also changed significantly. Although certain states, with their corrupt and despotic rules and rulers, create worldwide security concerns, non-state terrorist organizations continue to fish in troubled waters – most recently, Hamas and the Houthis. Although many of these non-state threats are not new, they are particularly threatening due to the weakened legitimacy and the fragile economic strength of the neomedieval states. Warfare in the neomedieval age has also experienced a revival of pre-industrial forms of warfare, including the privatization of military combat groups, the rise of brigades of mercenaries (bands), the spread of sieges, irregular, protracted, and frozen conflicts, civil wars, and the formation of informal coalitions consisting of various state and non-state actors.

Of course, these trends do not necessarily imply that we are on our way to a new feudal era one-on-one. New technologies lacking historical precedents will emerge. However, as the echo of the last fifty years of modern and postmodern growth fades, a marked decline will characterize the neomedieval era. In the future, human life will once again become “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”, as Hobbes phrased it in the 17th century.

SOURCES:

Welcome to the “Neomedieval Era”

By Joshua Keating

In: VOX, 06.02.2024

The Annals of Flodoard of Reims 919-966

Ed. and tr. af Steven Fanning og Bernard S. Bachrach

University of Toronto Press 2011.

READ MORE:

U.S.-China Rivalry in a Neomedieval World. Security in an Age of Weakening States

by Timothy R. Heath, Weilong Kong, Alexis Dale-Huang

Rand Research Report 2023