When did the war on wolves commence? Only in the later Middle Ages, it appears. On the contrary, poetry, sagas, onomastics, and pictorial art were rich in the motif of the wolf and the man and their myriad metamorphoses.

The Early Medieval Scandinavian world from c. 400 – 1000 was known for its animal art and animistic landscapes. It appears, the vilification of wolves did not commence until the Later Middle Ages. In contrast, early Medieval Scandinavian wolves played and significant role as demi-gods and fabulous beings.

Thus, the two wolves, Hati and Sköll, were known to hunt the sun and the moon across the heavens until Ragnarök, when they would swallow both celestial bodies. According to Snorri, Hati and Sköll were sons of Fenrir and a giantess who lived in the wilderness in the ironwoods west of Midgard. Fenrir, a gigantic wolf known to have been shackled by Thor (who lost his hand in the process), is also known as the ferocious wolf, which at the end of the world, Ragnarök, kills and eats Odin. One of the earliest depictions of a wolf in a Scandinavian context is found on the bracteates depicting Thor, whose hand is devoured by Fenris (from Skrydstrup and Trollhättan). The same scene is also carved into the Gosforth Cross from the 10th century.

One particular motif was the wolfs known from the world of Odin. According to the narratives about Odin, he possessed two tame wolves, Gere and Freke. Known to scavenge among the dead warriors on the battlefield, these and other wolves were turned into Odin’s feisty warriors. Or rather, real-time Norse warriors were believed to shapeshift into úlfhédnar, wolf-warriors, akin to the berserkers, warriors who had shapeshifted into bear-warriors.

Such warriors were known to be fearless and to kill in the same manner as the wolf with its pack. We know what they looked like from the Torslunda-plaque, where an úlfhédnar (warrior dressed as a wolf) follows the figure of the so-called dancing Odin.

Likely the use of the personal name of Ulf or in high German Wolf (or compounds thereof) signified a wish to imbue the named person with the characteristics of a wolf-warrior. From the different names (heiti) and periphrases (kennings) used in the Scaldic verses, which were used to denote a wolf or wolves, we know they were dusky, dark-cheeked grey beasts and watchers, dwelling on the heaths or wealds (that is in the wilderness). Known to be noisy howlers, they would boast of their role as bear-like combatants (aka Beowulf).

In the anonymous Þulur, Vargas heiti, we encounter the wolf as a

Vargr, ulfr, Geri,

vitnir ok hninnir, grádýri,

Hati, Hróðvitnir

ok heiðingi,

Freki ok viðnir,

Fenrir, hlébarðr,

Goti, gildr, glammi,

gylðir, ímarr,

ímr ok egðir

ok skolkinni.

Enn heitir svá

ylgr: vargynja,

borkn ok íma,

svimul.

(Source Scaldic Project – Anonymous Þulur, Vargas heiti)

The importance of wolves is also demonstrated by the number of different kennings found and identified to denote wolves in the Scaldic poetry, 51 in all. As such, it ranks as the seventeenth most common kenning. Several of these kennings describe the wolf as the riding animal preferred by witches. Such a wolf is depicted at the Hunnestad-monument, where the jötunn Hyrrokin is riding a wolf (constructed in AD 985–1035).

Shapeshifting

In modern psychiatry, clinical lycanthropy is listed as a diagnosis identifying people who believe they can turn into wolves. Obviously, the ancient Norse did not see shapeshifting or shamanism as a clinical disorder. Probably, it was regarded more as a gift from the Gods and perhaps even wished for when children were called Wolf or Ulf. The belief that such transformations were possible continued to be present in folkloristic beliefs in the Nordic countries into the 19th century.

The old Norse texts – of which there are fourteen preserved in Icelandic texts and two Norwegian should be closely considered alongside the same stories of the figure of the man-bear from eight sources. One of the intriguing facts is that these stories may be found in the Icelandic texts, although neither wolves nor bears were known in Iceland.

The stories of shapeshifting more or less follow a strict form. According to these, a shapeshifting occurred when a man or a god put on a hamr, meaning pelt, skin or form. Through this “dressing-up”, the man or woman de facto becomes the animal. In a broader European context, such “persons” came to be called werewolves. However, this expression is not known from Anglo-Saxon texts before the 11th century, when Wulfstan used it in the Laws of Cnut. Nor is it known in a Scandinavian context until the Renaissance or later. Therefore, we may presume that by all accounts, Scandinavian shapeshifters simply became wolves. Also, the shapeshifter personally instigated such shapeshifting. No outside spell or enchantment was involved.

The Völsunga Saga

Central to the understanding of what shapeshifting consisted of in an old Norse context is the evidence from the Völsunge saga, also known as the saga of the “Ylfingar” or Wolflings. This saga involves several stories of shapeshifting, one of which tells the story of how Sinfjötli and his foster father, Sigmundr, find two magic pelts in a hut in the forest. These pelts, which can only be removed every ten days, unleash the warrior inside Sinfjötli. Perhaps an echo of the initiation rites known from other societies, the saga includes a narrative about other brothers who did not survive but were instead eaten by a wolf. The saga also holds the story of how Sigmundr later kills the dragon Fáfnir. This motif is known at least from ca. AD 1000 (Ramsundsristningen) but is also preserved in two fragments of Eddic poems as well as in numerous other European contexts, which are considered the sources for the saga.

Wolf and Warg

Curiously, the Germanic languages seem to possess two words for the wolf – wolf and vargr. And indeed, Varg is the present-day term for the animal in Sweden and Norway. However, this word does not seem to have a long and prominent history in Old Icelandic, Old Swedish or Old Norwegian. And is not found in old Danish. Neither is it found in old placenames or personal names in Scandinavia. This lack of Vargr in place and personal names in medieval sources is in direct opposition to the word “wolf”, which is found alone or as a part of a compound in numerous placenames and as a favourite personal name across Northwestern and Germanic Europe. Likely, the word first entered the Swedish and Norwegian vocabularies in the later Middle Ages, when the productive phases of placenames were basically over.

It has been speculated that the word, vargr, entered the vocabulary in the later Middle Ages as a euphemism to avoid saying the word “wolf”, which animal folklore tells us you call upon when you mention his name (“Wenn mann den Wolf nennt, kommt er gerennt”). However, this does not tell us why the word entered the Swedish and Norwegian vocabulary but not the Danish. We may only speculate, as the question seems not to have been dealt with in detail by Scandinavian philologists.

What we do know, though, is that the word warg or vargr, as opposed to wolf, had a decidedly different meaning in Late Antiquity and the Early Germanic Laws. Thus we meet the word in Wulfila’s translation of the Bible into Gothic, where Jesus is gawargjand – condemned – to death, while the noun damnatio is termed wargiþa or gawargeins. Later, in the writings of Sidonius Apollinaris we meet the term vargus/varguses denoting highwaymen who had abducted a woman. After that, we meet the word in the early germanic law, Lex Salica, in the first part recently re-dated to the end of the 5th century. This text contains both the verb wargare and the noun wargus. The latter is here explained as a person who is expelled and whom no one, even family, is allowed to shelter or feed until he has paid his debt accrued for despoiling or robbing a grave. Hence, a wargus is an outlaw, bandit, scoundrel (or just vagrant). The verb – in the form wagaverit – is here glossed by plagiavit and means kidnapping (qui eum servum plagavit, hos est wargaverit; from Pactus. Leg. Sal., tit. 66 §4). The same meaning may be found in the later Lex Ribuaria (7th century), which is based on Salic Law.

The conclusion is that warg from the 6th century was glossed as a malefactor. However, it was not until five centuries later that the idea of the wolf in Old Norse was tainted with the vargr’s continental connotations. Although likely inspired by the concept already present in Lex Salica that the malefactor or outlaw had to go to the forest (per silvas vadit), the meaning of vargr as wolf was decidedly secondary. Later we meet the same idea in words used to denote expelled persons, the wealdgenga in the Anglo-Saxon sources and skōgarmađr in the old Norse sources.

This conclusion allows us to understand the fluid movement of shapeshifting between men and wolves (or bears, birds and other ferocious animals) in the North as something which was only much later tainted with the ideas of outlawry or crimes. Rather, shapeshifting was, in the Old Norse World, a way of moving across liminal boundaries between the settled landscape and the wilderness – the Wald or the Weald. Likely, this also explains the shapeshifting of Beowulf when attacking Grendel, which he does in a regular fistfight. Beowulf is here shapeshifting to meet the monster, also called the water-wolf.

To conclude: The wolf may have been regarded as a wild creature in Early Medieval Scandinavia. But he or she was not an eternally lost or condemned being as was the case after the church introduced the concept of the irredeemable vargr as the personification of the devil. Until then, wolfs might still become men, while men might turn into wolfs.

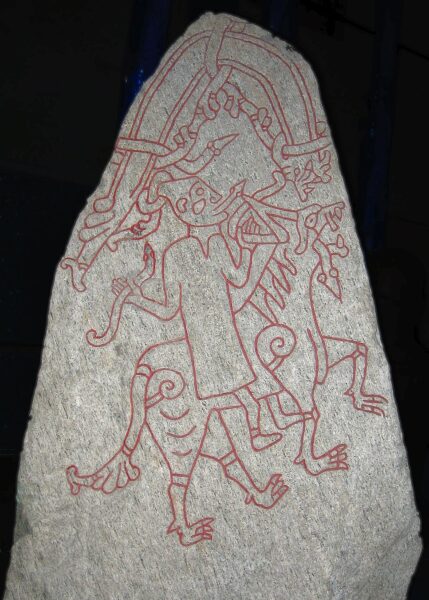

FEATURED PHOTO:

Fenrir and Naglfar on the Tullstorp Runestone. The inscription mentions the name Ulfr (“wolf”), and the name Kleppir/Glippir. The last name is not fully understood, but may have represented Glæipiʀ which is similar to Gleipnir which was the rope with which the Fenrir wolf was bound. The two male names may have inspired the theme depicted on the runestone.© Sven Rosborn (CC).