A new project by the Danish designer Jim Lyngvild aims to visualise our Viking kings and queens. But what did they really look like?

Jim Lyngvild is a creative Danish designer famous for his colourful and inspiring renditions of our Viking ancestors. Recently he has been engaged in spiffing up the exhibition of Vikings at the National Museum in Copenhagen. In a new project, he aims to visualise what the early Danish kings and queens looked like. No doubt, these photos will in the future add spice and joy to the dull and perhaps too “wordy” presentations offered by scholarly books and exhibitions, which flood the market. The question, though, is what may we know?

Figurative language

The short answer is: not very much. Vikings lived in an oral society with very limited use of literacy. Although the use of runic writings was probably much more widespread than we tend to believe, the evidence points to a purely epigraphic use on artefacts or stones, indicating ownership or commemorations. At least, this was the case until runes were adopted on the birch-bark letters found in Bergen and Novgorod from c. 1150 – 1350. In this Viking world, any portraits were substituted by masks, or “painted” with highly elaborate wordplay in the form of scaldic “kennings”, a distinct figurative language known from the preserved poetry.

Which means, we simply don’t know much about what Viking kings looked like before the adoption of Christianity and the accompanying manuscript culture. And even then, we may only see them disguised as ideals.

Cnut the Great

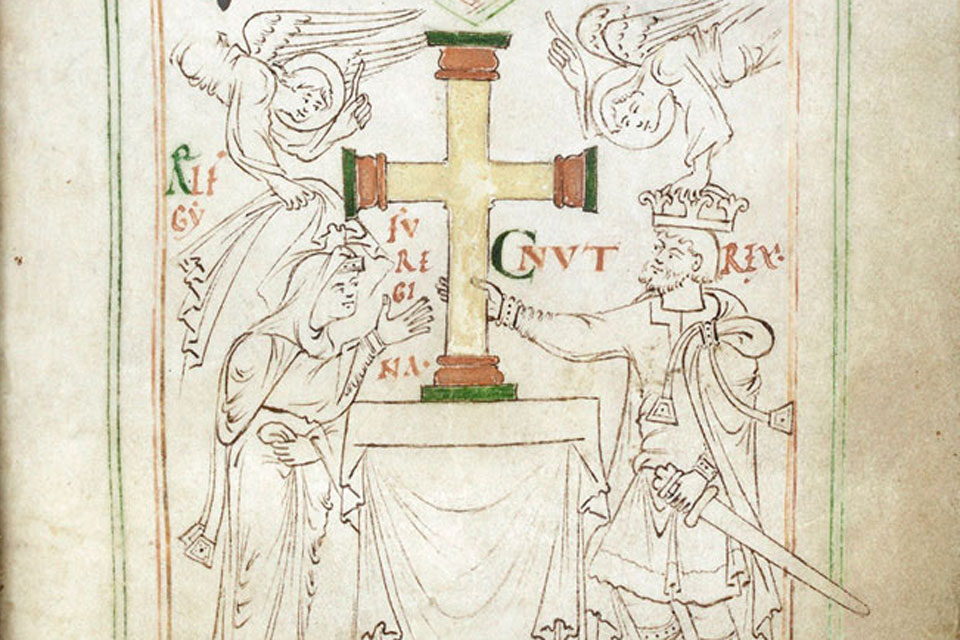

The earliest rendition of a Scandinavian king pictures Cnut the Great (c. 990 – 1035) and his queen Emma (c. 985 – 1052) in the miniature, which may be found at the frontispiece of the Liber Vitae of the New Minster at Winchester[1]. Here the king is painted flanking an altar, upon which is placed a large golden cross. Dated to c. 1031, it belongs to the group of so-called “presentation miniatures”, of which the earliest Anglo-Saxon depicts King Athelstan from the beginning of the 10thcentury. The genre is also known from Ottonian manuscripts from the 10thand 11thcentury Germany.

We know that Cnut received a silk robe and expensive garments when he visited Rome in 1027 to bear witness to the coronation of Conrad II (c.990 – 1039). It is probably also significant to note that his daughter was later married to Henry III (1017 – 1056). We also know that he travelled widely across Europe catering for his contacts among the French, the Burgundians and the Flemish.

This might tempt us to find a close affinity between the clothes, Cnut is wearing in the miniature and that of his German imperial kindred and wider network. Looking closer, however, should make us pause.

In the miniature, Cnut is dressed in a short tunic while carrying a somewhat old-fashioned sword. The tunic – which is not along ceremonial robe – has broadband at the neck as well as at the lower edge. His sleeves are likely fitted with embroidered and perhaps bejewelled wrists, as are his leggings. A high-ranking Viking at Mammen was laid to rest c. 970-71 in what was probably a woollen tunic, which sported similar wristbands as that of the king. The cuffs from Mammen were woven in tablet technique using gold. Afterwards, they were padded with wool and lined in silk, mimicking golden bracelets. Whether or not, the king is wearing such cuffs or metal clasps cannot be decided by studying the drawing. Both options are possible.

In the miniature, the king is also depicted as wearing socks or hoses fitted with similar bands at the top. Perhaps these socks were naalbound (looped needle-netting)? Usually, miniaturists would indicate that legs would be covered in cross-bound leggings. But here we see the king sporting either socks or hoses.

Especially interesting is the king’s cloak, which is fastened with a brooch or ring and decorated with a pair of flowing bands with large rhomboidal endings. The drawing seems to indicate that the ring is fastened to the tunic, with either the corner of the cloak tugged through the ring. Or a dangling band looped through the ring or brooch. The latter is probably the correct understanding. Such a ring is depicted in a drawing of Otto II from a manuscript from c. 1112-14[2]and may probably be found as well in other illuminations of Ottonian emperors.

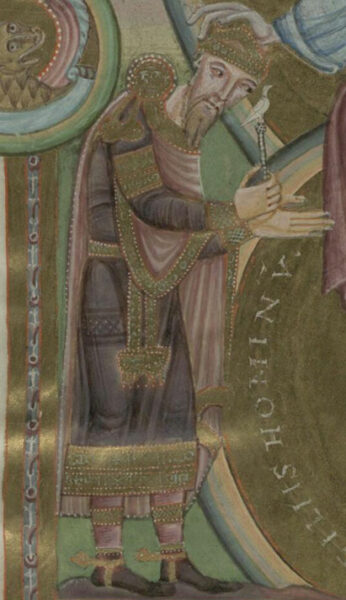

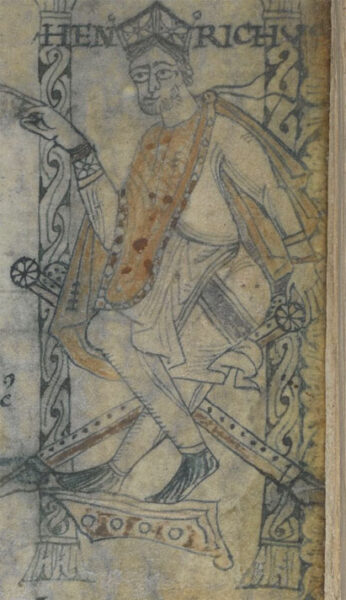

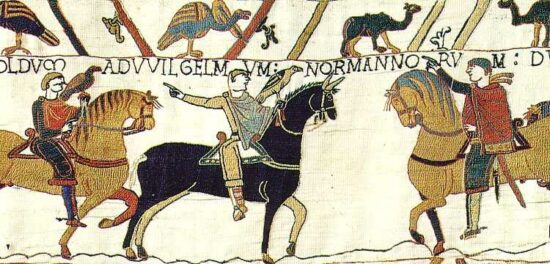

The flowing or dangling bands may be compared to a pair of similar strips found in the 10thcentury burial in Mammen. Such bands may also be indicated in a contemporary drawing in an Italian illumination from c. 985, depicting the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor, Otto II. In the same image, the emperor is portrayed holding what looks like a typical Viking sword with its somewhat old-fashioned three rounded lobes. Soon, these were destined to be replaced with more modern, fully rounded pommels. Another painting[3], where an emperor – this time Henry III – features a cloak, embellished with flowing bands may be found in one of his so-called Golden Gospels, the Codex Caesarius Upsaliensis from c. 1050. However, this rendition of the emperor is even more enticing. Perhaps the flowing bands are not made of embroidered or worked textiles, but rather as dangling “metal bling” fastened to a brooch like the one recently discovered at Fæsted in Denmark in 2016. Based on its Jelling style, this brooch has been dated to the reign of Harold Bluetooth (c. 950 – 86). Finally, similar bands can be found on a vignette from the Bayeux tapestry c. 1080, depicting William meeting up with Harold in Normandy. In this scene, William is riding a stallion and followed by an armed retinue, while Harold is leading a hunting party. This depiction dates from approximately the same time as the image in a Parisian manuscript of the seated Henry I of France.

To conclude: such bands may be found in a series of archaeological contexts and pictures:

- Fæsted in Jutland c. 960 – 85

- Mammen in Jutland c. 970

- Rome c. 985

- Winchester c. 1031

- Goslar in Germany c. 1050

- Paris c. 1072 – 79

- The Tapestry of Bayeux c. 1080

Whether made of textiles or in the form of golden bling attached to brooches, it seems fair to conclude that such bands or strips might have been significant and traditional signs of rank or honour carried by kings, emperors or high-ranking members of their retinue – inside Scandinavia and outside. And for more than a hundred years.

All these elements point towards the “Scandinavian character” of the King’s dress, writes Gale Owen-Crocker, who has dealt in details with the clothes of both Cnut and Emma. She points out that even the shoes of Cnut seem to be “Scandinavian”. Similar design has been found in Viking contexts in Ireland, Scandinavia and Russia.

But was his dress really “Scandinavian”? Or was it rather Continental? Or German? Or perhaps just a bit old-fashioned, intended to send a signal as to his veneration for his roots and his rank?

The Sword

The sword, Cnut carries in the vignette from Winchester, may offer an answer. We cannot claim that it is a Viking sword. The drawing of the weapon in the hand of the king does not indicate the embellishment or style of the overlaid decoration of the pommel, the hilt, or the grips. Animalistic, if Viking, or (perhaps) plant ornaments if “Christian” (Frankish). What we do see, though, is a sword with a straight guard and a pommel made with three lobes, such as was the fashion in the second half of the 10thcentury (type Petersen S – dated to c. 930 – 1000).

With its straight guard and lobed pommel, it reminds us of the swords carried by the Ottonian rulers in the 10thcentury before they were reconfigured as parade swords. This was the case with the so-called sword of St. Maurice, which was probably gifted to the cathedral in Magdeburg, which had it transformed into a processional sword. According to a recent study by Mechtild Schulze-Dörrlamm, this sword belonged to the types V or W. Compared to this is the sword held by Otto II in the abovementioned coronation portrait from c. 985.

Maniples

All-in-all, Cnut’s dress seems to belong to both a Scandinavian and German tradition, demonstrating the cultural commonality between the neighbouring powers in the 10th and 11th centuries. Perhaps, though, the hanging bands have yet another meaning. We know Cnut liked to appear as pious as his European colleagues. This is evident not only from his portrait in the Liber Vitae, but also from other written testimonies from his grand tour to Rome. We also know that the man from Mammen sported at least some evidence in his grave. Although furnished, a lightened candle was found as part of the equipment. It is likely this was a symbol of his Christian affiliation.

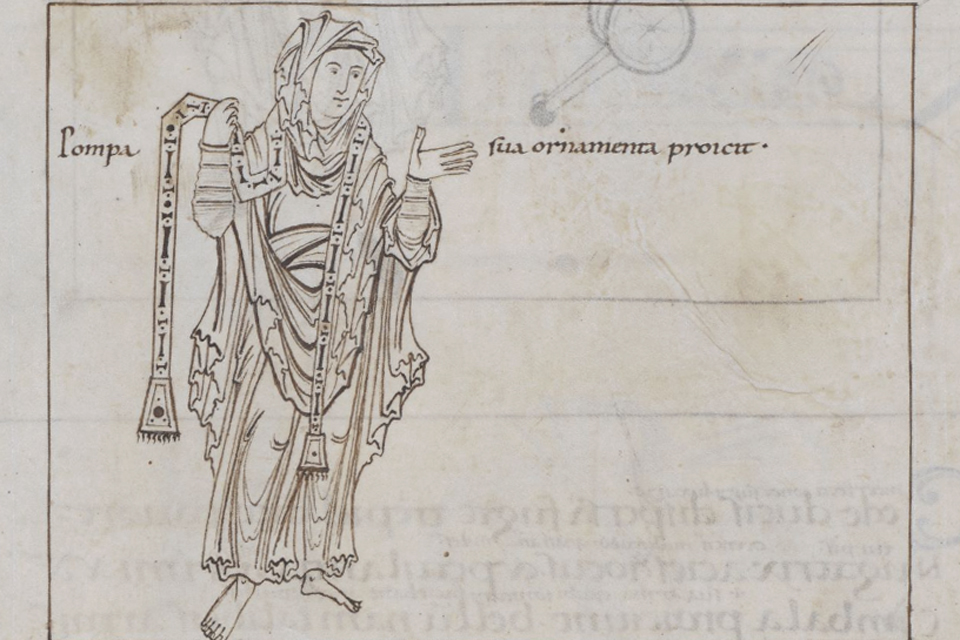

Might the hanging bands be another such symbol? in short a maniple, donated to Christian converts of a certain status? Looking once more at the portrait of Cnut and Emma, we notice she has two bands hanging down her back. They mirror those of her husband’s. Another curious drawing of a woman sporting such hanging bands is found in a manuscript (British Library, Add MS 24199) rendering the Psychomachia of Prudentius, in which the personified virtues of Hope, Sobriety, Chastity, Humility, etc. fights the personified vices of Pride, Wrath, Paganism, Avarice, etc. One of the evil characters is Pompa Ostentatrix, who literally flaunts her pomps and circumstances in the form of a billowing maniple, akin to those worn by priests.

Might the bands be coveted Christian symbols of the kings in the 11th century, aspiring to sainthood – as some of them arguably did? Perhaps Jim Lyngvild really gets us closer to what a Very Christian Viking King might have looked like?

NOTES:

[1]British Library, MS Stowe 944

[2]Kaiserchronik. Corpus Christ College, Cambridge, Ms. 373, fol 47r

[3]From Codex Caesarius Upsaliensis c. 1050 (former Goslariensis), fol 10. Photo: University of Uppsala.

SOURCE:

Pomp, Piety, and Keeping the Woman in Her Place: The Dress of Cnut and Aelfgifu-Emma

ByBy Gale R. Owen-Crocker

In: Medieval clothing and textiles. Vol. 1. Edited by Robin Netherton and Gale R Owen-Crocker. Boydell Press, 2005. Pages 41 – 52.

The Performance of Piety: Cnut, Rome and England

By Elaine Treharne

In: Francesca Tinti, ed., England and Rome in the Anglo-Saxon Period (Brepols, 2014), pp. 343-64

READ MORE: