Major exhibition summer 2015 in Torgau in Germany tells the story about the collaboration between Martin Luther and his protectors, the Saxon dukes

Without the early protection of the Saxon princes, Frederick the Wise (1483 – 1525) and his brother John the Constant (1468 – 1532), Luther might never have escaped the persecution of the Pope and the Holy-Roman Emperor. But who were those princes? An impressive exhibition in Torgau this summer tells their history.

The Theses 1517 – 2017

© Fondation Martin Bodmer, Cologny (Genève)

Foto: Naomi Wenger

In 1517 Martin Luther posted his 95 theses on the church door in Wittenberg. This event was later celebrated as the decisive moment, which started the Protestant reformation. Although nothing but an ordinary invitation to a university disputation, these theses nevertheless plunged Europe into a series of revolutionary changes, which we still live with. In 2017 the 500-year anniversary of the event is celebrated all over the world. A huge exhibition in Torgau this summer focuses on the role of the German princes and leads up to these festivities.

In order to understand, what the exhibition is all about, it is necessary to recapitulate a few facts. When Martin Luther posted his theses on the church-door, he also posted them by mail to the Archbishop of Mainz. These theses were very critical of the practice of selling indulgences, which was one of the key incomes of the Archbishop – who had bought his position from the Pope. Fundamentally Luther opposed the Roman Catholic doctrine that the grace of God could be bought as one might buy a pair of shoes. The justification of God was instead to be understood as a gracious gift of God granted to the faithful. This was initially the main reason Martin Luther was met by the series of events, which led to his excommunication and the Diet of Worms in 1521. Even though he had been promised safe-conduct in and out of Worms, he had to leave before he was sentenced to be burned. Afterwards he was kept safe at Wartburg under the disguise of “Junker Jörg”; protection was provided by Frederick the Wise, elector of Saxony. It was at Wartburg he translated the New Testament from Greek to German.

In spring 1522, however, he returned to Wittenberg and during that year he – amongst very many other projects – was engaged in preaching to the younger brother of Frederick, John the Constant, who was personally challenged by the dilemma of how Christians should balance between on one hand their conscience and on the other hand the due, they owed their lords and masters ( in his case the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor). And parallel to that: the prince was also confronted with the dilemma of how personally to live in accordance with his Christian faith – and more specifically the tenets of the Sermon of the Mount – and at the same time exercise his worldly power.

Two Kingdoms Doctrine

In December 1522 Luther published a small pamphlet with the tile “Von Weltlicher Obrigkeit, wie weit man ihr gehorsam schuldig sei” (About secular powers and to what extent one should be obedient. [1]) In the booklet, Luther explained a number of fundamental tenets, which came to have paramount effect on the future of not only the Evangelical church, but in fact the whole of Europe. (It still sets its mark in the 21st century on how Evangelical Lutheran churches should play together with the surrounding states). First of all Luther explained how God had instituted secular powers in order to secure peace and prosperity as well as the punishment of criminals. Secondly Luther explained the actual limits to the wielding of this power. Finally he wrote how a Christian prince should go about his business.

The small booklet – which were soon followed by others touching upon the same matters – has often been characterised as a kind of Evangelical manual for Princes, much like the mirrors, which were a common medieval genre since Smaragdus of Saint-Mihiel wrote his “Via regia” in 813 and dedicated it to Louis the Pious.

Fundamental to Luther was the obligation of any conscientious Christian man or woman to distinguish between on one hand the soul and on the other hand his body, wealth and honour. In these last matters, he or she would be obliged to be obedient according to the law of the land. As to the soul, he or she owed his allegiance to none but God,. Building on this, Luther outlined how a Christian prince should behave in order to secure all his people the freedom to live according to his personal understanding of the Gospel.

One result was the confirmation of a new way of organising the local life in parishes. In short parishioners were granted the right to call, whichever theologian they wished to serve as their local vicar. His obligation was on the other hand to collaborate with the magistrates and local powers in order to secure that life in the parish was lived in accordance with the law of the land.

Another – and in this connection more important – result was the fact that the princes and their local lords or magistrates were given a rationale to live conscientiously at peace with their business of “ruling”. As Luther wrote: “A prince should carry out his work in four ways 1) faithfully and prayerful towards God 2) towards his people in love and with Christian subservience 3) towards his council and lords with personal reflection and independent judgements and 4) against criminals with cautious, but firm strictness.” Just as every man and woman whether cobblers, merchants or servants were called by God to fulfil their existence in accordance with their positions and profession, princes were called to do “their job”, which was ruling.

Exactly how this ideology came to frame the he political events and the way of life of the German princes in the 16th century is the theme of the exhibition. More specifically it focuses on the life-world of the ducal families of the Ernestines and Albertines In Sachsen.

Torgau

The exhibition is very pleasantly organised in Torgau in one of the best preserved castles from that period, Hartenfells. Here visitors may for the first time see the private rooms of the dukes of Saxony as well as the Electorial Chancery and the office of the Superintendent (the bishop).

Of special importance is of course the Palace Chapel, which has been recently restored to its former glory. Martin Luther consecrated it in 1544. It was one of the first protestant church-buildings built in accordance with the ideas of the reformers in Wittenberg.

The exhibition lists more than 250 exhibits, ranging from some precious relics like the personal ring of Martin Luther to the princely mitre of the Archbishop of Brandenburg. In between it shows an impressive selection of not only sculptures, paintings, coins, medallions, ceremonial cups and other art-work, but also weapons, armours, clothes and personal objects. All this is liberally mixed with a profusion of original letters and printed publications authored by Martin Luther plus the propaganda leaflets, which became such a distinctive feature of the time.

The exhibition is generously accompanied by a catalogue and a companion-volume with a number of important essays outlining the life-world of the Saxon princes and their protégée, Martin Luther. (Unfortunately this publication is only available in German). The essays are the result of a scholarly conference held in Torgau in 2014.

This exhibition is worth much more than a detour. Together with the exhibitions this summer focusing on the works of Cranach, it should be the impetus to follow in the footsteps of the reformer before the trail gets swamped in 2017.

Notes:

[1] Von Weltlicher Obrigkeit, wie weit man ihr gehorsam schuldig sei. Wittenberg 1523

From: Luther Deutsch. Die Werke Martin Luthers. In neuer Auswahl für die Gegenwart, Ehrenfried Klotz Verlag 1967, Vol. 7, pp. 9-51. (English translation: Luther’s Works, 55 vol. edited by Jaroslav Pelikan and Helmut T. Lehmann (1955-76). Vol. 45) Own translation.

VISIT:

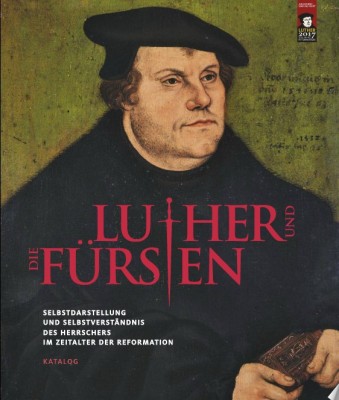

Luther und die Fürsten. Selbstdarstellung und Selbstverständnis des Herschers im Zeitalter der Reformation

Torgau, Schloss Hartenfells

15.05.2015 – 31.10.2015

The City of Torgau in Sachsen -Anhalt

CATALOGUE:

Luther und die Fürsten. Selbstdarstellung un dSelbstverständnis des Herrchers im Zeitalter der Reformation. Vol. 1 – 2

Luther und die Fürsten. Selbstdarstellung un dSelbstverständnis des Herrchers im Zeitalter der Reformation. Vol. 1 – 2

Ed. by Dirk Syndram, Yvonne Wirth and Iris Yvonne Wagner

Staatlichen Kunstsammlung Dresden, Sandstein Verlag 2015

ISBN 978-3-95498-160-1

READ MORE:

The Emperor and the Electors in Late Medieval Germany

FEATURED PHOTO:

Exhibition in Torgau 2015 © Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Photo: Oliver Killig