In the Middle Ages, mercenaries were widely recruited. However, what was the military effectiveness of these forces? And the downside?

In 1364, Valdemar IV of Denmark travelled through Europe to end up in Avignon. During his stay there, the French King, Charles V, approached Valdemar to hire him and his army as mercenaries, trying to embroil Denmark in the Hundred Years’ war. Although nothing came of these plans, such negotiations were part and parcel of the continued hostilities between France and England after 1337 and the later battles at Crécy, Poitiers and Agincourt. Playing out during the fateful years of the Black Death, soldiers and armies were in constant demand. Moreover, Valdemar was internationally known as a brilliant soldier and tactician.

It would have been a coup. At this point, in 1364, hostilities were resuming. John II, the unlucky French King, captured at Poitiers in 1356, had died in London, and the unpaid ransom demanded by the English Crown defaulted. Slowly, this created a breathing space for the French to gather pace, rebuild the countryside and recover some strength to regain the upper hand. These manoeuvres also involved a rebuilding of the French army, which had repeatedly lost out to the clever strategies and tactics employed by the English. One of the ways forward for the French army was to employ mercenaries. The question is, to what extent this military format made sense?

The Genoese Crossbowmen

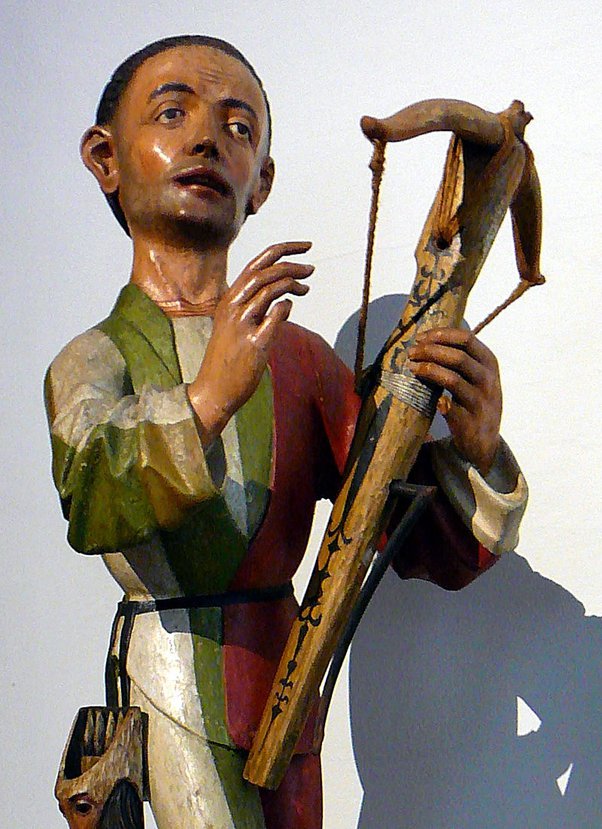

One of the first instances of free companies recruited into the French army in the 14th century were the Genoese crossbowmen engaged to counter the attacks mounted by the English archers. These soldiers were armed with crossbows, balestrai, and led by Italian commanders or warlords, who organised, led and rented out their so-called “free companies”. However, as opposed to Italy, where the companies were often constituting the whole army of a city-state, the Genoese crossbowmen, led by Carlo Grimaldi and Antonio Doria, were enrolled or built into the French army, which was organised around the “semonce de nobles”, the calling upon the nobility to fulfil their feudal obligation and the arrière-ban, a general albeit semi-voluntary conscription.

One of the first instances of free companies recruited into the French army in the 14th century were the Genoese crossbowmen engaged to counter the attacks mounted by the English archers. These soldiers were armed with crossbows, balestrai, and led by Italian commanders or warlords, who organised, led and rented out their so-called “free companies”. However, as opposed to Italy, where the companies were often constituting the whole army of a city-state, the Genoese crossbowmen, led by Carlo Grimaldi and Antonio Doria, were enrolled or built into the French army, which was organised around the “semonce de nobles”, the calling upon the nobility to fulfil their feudal obligation and the arrière-ban, a general albeit semi-voluntary conscription.

Weighing the effectiveness of the French armies deployed at Sluis (1340), Crecý (1346), Poitiers (1356) and Agincourt (1415) and their devastating defeats, the military historians have not so much pointed to the composite character of the French navies and armies as the innovative military tactics by Edward III, the Black Prince and later Henry V, utilising their archers and the new artillery (canons) to their utmost capabilities. However, as much of the military history has been written by English historians, the evidence has been marshalled to explain their victories – clever military strategists, better commanders, and more unified soldierly spirits turning the tables against the large but ineffective armies of the French. However, what role did the “companies” really play? It appears the evaluation of the Genoese Crossbowman has varied. Thus, at Crècy, they were afterwards blamed for the catastrophe. However, contemporary witnesses tell us that they were mainly unsuccessful because of the defensive position created by the wagons behind which the English archers were lined up. And the following melee created by the French cavalry.

“The first division with the Genoese crossbowmen advanced towards the King of England’s wagenburg and started shooting their quarrels. But immediately, they were subjected to counter-shot: the carts and below them were protected from bolts by fabric and draperies, and in the King of England’s divisions inside the wagenburg and in the others already deployed stood 30,000 English and Welsh archers. Every time the Genoese shot a bolt from their crossbow, that bolt would be answered by three arrows from their bows, which formed a storm cloud in the sky. And these did not fall without hitting men and horses. To these, one must add the shots from the bombards, so loud and threatening that it seemed God himself was thundering, with the great killing of men and gutting of horses. But worse for the French forces, the narrow tight fighting area was as wide as the opening of the wagenburg. And then, the second division led by the count of Alençon hit and shoved the Genoese, pushing them towards the carts so that they could neither hold their ground nor shoot their crossbows, being constantly hit by the arrows of those on top of the carts and blasted by the bombards, so that many were killed or wounded. For this reason, the crossbowmen described above, were crammed together and pushed towards the wagenburg by their own knights, and they turned and fled. The French knights and their sergeants, seeing them run, believed they had been betrayed and so killed them, with few surviving.”

(From Giovanni Villani: New Chronicle. Quoted from: The Battle of Crécy: A Casebook. By Michael Livingston, p. 117-19)

The Infamous Routiers

One of the main discussions would later focus on the trade-off between the gain of military expertise, experience and manpower versus the lack of loyaltyamong the mercenaries. Later, this led to a famous characterisation by Machiavelli of the mercenary armies as “useless and dangerous”. However, as skilled professionals, it does appear the French kings did not hold the defeats against their mercenary companies but continued to employ them during the next hundred years. As was the case with Valdemar, the French King was constantly looking to recruit potential soldiers of war and their armies.

However, on one count, the mercenaries became a significant setback. Lacking money and pay, the mercenaries’ income in between employment tended to be outsourced as a kind of license to pillage, take hostages, demand ransoms, thus adding significantly to the misery caused by the English. It appears the war went on, but nobody went home. Thus, this was the case after 1360, when the treaty of Brétigny was finally signed. Simply, the mercenary companies refused to disband. Instead, they formed larger companies with perhaps 15.000 men bent on ravaging the countryside.

Especially, the German mercenaries, as well as mercenaries and adventurers from Brabant, Gascony, Flanders, Hainault, Breton and France were left to fend for themselves. In Champagne, they captured the castle of Joinville, seized a considerable amount of booty for ransom before the mercenaries moved on to pillage the bishoprics of Langres, Toul and Verdun. From here, they moved south plundering Vergy and Gevrey-in-Beaune and in general ravaging the region. Estmates indicate thousands were roaming Burgundy and Macon. In the end, the Pope at Avignon called for a crusade against the marauders. However, the crusaders found it too lucrative not to join up. Failing this, King John II finally paid them off and sending them back to Italy and Gascogne.

Perhaps, this is the main downside. In the end, mercenaries turn on their employers and their people.

FEATURED PHOTO:

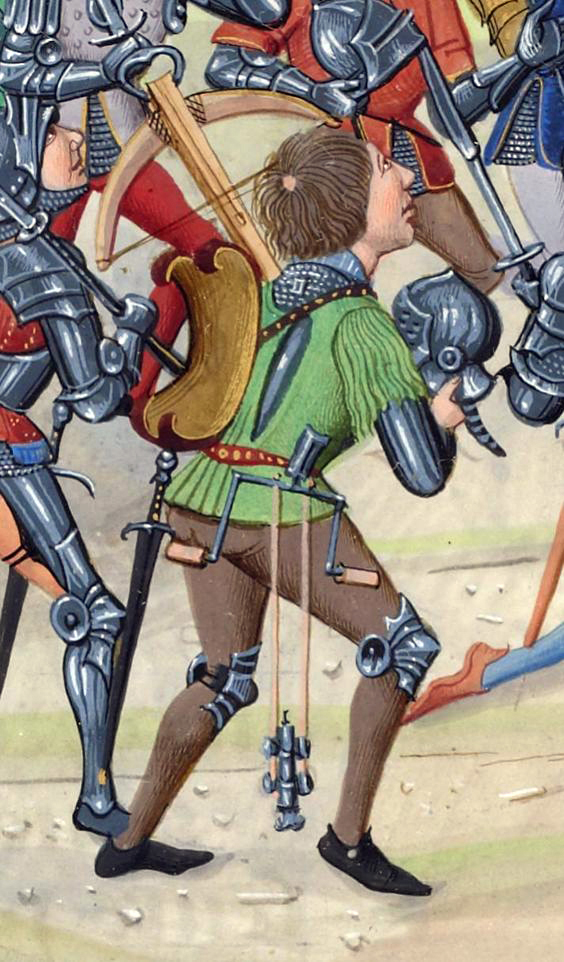

The routiers from Ghent capture and pillage Grammont Jean Froissart, Chronicles, fol. 135r. BNF, FR 2644

SOURCE:

‘Useless and dangerous’? Mercenaries in fourteenth century wars

By Matteo C.M. Casiraghi

In: Small Wars and Insurgencies (2022) Vol 33: 1-2, pp. 71-91