The aDNA studies of the Avars, a Mongolian people who settled in the Carpathians in the 6th century, continue to yield new and fascinating insights into the formation of close-knit ethnic groups.

Since the adoption of the “ethnogenesis” and “creolization” by anthropologists and historians in the post-war showdown with the racial theories dominant in the pre-war period in the 20th century, it has been politically incorrect to claim that distinct ethnic groups might be delineated as anything other than the result of cultural creative processes.

The interdisciplinary studies at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology of the aDNA of the Avars buried in the Carpathians in the 6th and 7th centuries however, are currently providing insight into the role kinship and matrimonial policies played in the formation of the Avars as a distinct ethnic group and their social dynamics.

The Avars

Earlier studies have documented how the Avars came from Eastern Central Asia (Mongolia) from the East Asian and Pontic steppes to rule much of Eastern Central Europe for a quarter millennium, from approximately AD 567 to 796. However, we do not know to what extent, if at all, these people maintained their steppe traditions. Neither do we know how and to what extent the newcomer groups from the East interacted with each other and with the population of their new homeland in Europe. In essence, how did their way of life change over time in a completely new environment after they left the steppes and abandoned their nomadic way of life?

Thus, while considerable historical knowledge on the Avar period populations was passed on to us by their enemies, mainly the Byzantines and the Franks, we lack information on the internal organisation of their clans and their social fabric. Women are particularly underrepresented in these historical sources, with only three incidental mentions, so knowledge of their lives is practically non-existent. On the other hand, in their cemeteries, they left one of the richest archaeological heritages in European history, including around 100,000 graves that have so far been excavated. Part of this material has been explored to oncover the social fabric of the Avars.

Archaeogenomics

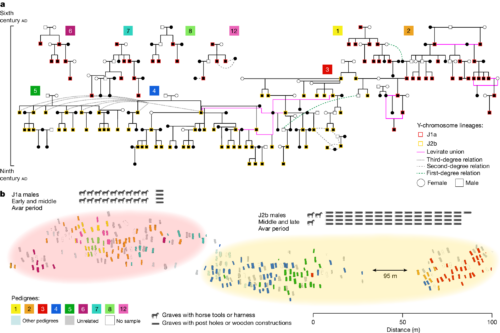

The new study involved analysing entire communities by sampling all available human remains from four fully excavated Avar-era cemeteries, analysing a total of 424 individuals from an archaeogenomic perspective. This analysis has revealed that around 300 of these individuals had a close relative buried in the same cemetery and that the kinship between these 300 individuals covered six to nine generations. Thus, the scientists have been able to reconstruct one extensive pedigree, which is nine generations deep and spans about 250 years.

The study has also uncovered how the Avars practised a strict patrilineal system of descent, and that women played a key role in promoting social cohesion, linking individual communities by practising exogamy (marrying outside their original community). Also, polygamy with multiple reproductive partners was common. Several independent cases show that these communities practised so-called levirate unions. This practice involves related male individuals (siblings or father and son) having offspring with the same female individual. Guido Alberto Gnecchi-Ruscone, the primary author of the study explains how ”these practices, together with the absence of genetic consanguinity, indicate that the society maintained a detailed memory of its ancestry and knew who its biological relatives were over generations”.

![Burial with a horse at the Rákóczifalva site, Hungary (8th century AD). This male individual, who died at a young age,… [more]© Institute of Archaeological Sciences, Eötvös Loránd University Múzeum, Budapest, Hungary](https://www.medieval.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/WEB-Avar-burial-c-Institute-of-Archaeological-Sciences-Eotvos-Lorand-University-Muzeum-Budapest-Hungary-411x600.jpg)

© Institute of Archaeological Sciences, Eötvös Loránd University Múzeum, Budapest, Hungary

One community appeared to present another story characterised by a marked genetic discontinuity. Simply put, the population had been replaced by another featuring the same ethnic and social. This was revealed by the shift from one patriline to another and by changes in patterns of distant relatedness (the network of genetic relatedness, i.e. the IBD-network). Zsófia Rácz, co-first author of the study, says: “This community replacement reflects both an archaeological and dietary shift that we discovered within the site itself, but also a large-scale archaeological transition that occurred throughout the Carpathian Basin”.

This change – probably related to local political realignment – was nevertheless not accompanied by a change in ancestry and would therefore have been invisible without the study of whole communities. The finding highlights how genetic continuity at the level of ancestry can still conceal replacements of whole communities and has important implications for future studies comparing genetic ancestry and archaeological shifts.

HistoGenes

The research project, HistoGenes, has been funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 856453 ERC-2019-SyG HistoGenes). HistoGenes is a research framework investigating the period of 400 to 900 CE in the Carpathian Basin from an interdisciplinary perspective.

The recently published study by a multidisciplinary research team of geneticists, archaeologists, anthropologists and historians, including researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, the Institute of Archaeological Sciences and Department of Biological Anthropology at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Institute of Archaeogenomics, HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities, Budapest, Hungary, the Curt Engelhorn Center for Archaeometry in Mannheim, Germany, the Institute for Austrian Historical Research of the University of Vienna, Austria, the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, USA, and others.

FEATURED PHOTO.

Excavation works conducted by the Eötvös Loránd University at the Avar-period (6th-9th century AD) cemetery of Rákóczifalva, Hungary, in 2006. © Institute of Archaeological Sciences, Eötvös Loránd University Múzeum, Budapest, Hungary

NOTES:

(1) Proper Peasants. Traditional Life in a Hungarian Village. By Edit Fél and Tamás Hofer. Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology, Vol 47. New York 1969.

SOURCES:

Network of large pedigrees reveals social practices of Avar communities

By Guido Alberto Gnecchi-Ruscone, Zsófia Rácz, Levente Samu, Tamás Szeniczey, Norbert Faragó, Corina Knipper, Ronny Friedrich, Denisa Zlámalová, Luca Traverso, Salvatore Liccardo, Sandra Wabnitz, Divyaratan Popli, Ke Wang, Rita Radzeviciute, Bence Gulyás, István Koncz, Csilla Balogh, Gabriella M. Lezsák, Viktor Mácsai, Magdalena M. E. Bunbury, Olga Spekker, Petrus le Roux, Anna Szécsényi-Nagy, Balázs Gusztáv Mende, Heidi Colleran, Tamás Hajdu, Patrick Geary, Walter Pohl, Tivadar Vida, Johannes Krause, Zuzana Hofmanová.

In: Nature, 2024;

Press release: Decoding Avar society

READ ALSO:

READ MORE: