For the last thirty years archaeologists have excavated at Gl. Lejre, discovering an impressive series of seven great halls, succeeding each other for 500 years.

Because I have heard marvellous things about their ancient sacrifices, I will not allow these to pass unnoticed. In those parts, the centre of the kingdom [of the Danes] is a place called Lejre, in the region of Seeland. Every nine years, in the month of January, after the day of which we celebrate the appearance of the Lord [6 January], they all convene here and offer their gods a burnt offering of ninety-nine human beings and as many horses along with dogs and cock – the latter being used in place of hawks. As I have said, they were convinced that these would do service for them with those who dwell beneath the earth and ensure their forgiveness for any misdeeds.

Thietmar of Merseburg, Book 1: 17. Here quoted from: Ottonian Germany. The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg. Translated and annotated by David A. Warner. Manchester University Press 2001, p. 80

Thietmar was Bishop in Merseburg, a German city south of Magdeburg on the river Elbe. However, he was also the author of a famous chronicle, which he wrote from 1013–1018, and which deals with the events not only in Ottonian Germany but also among its neighbours. One of these was the Kingdom of Denmark, which at that time (during the reign of Canute the Great) had expanded into a northern empire comprising England, Denmark, Norway and parts of present-day Sweden. Given this, it seemed pertinent for him to tell the story about Lejre quoted here.

A wild scene, most commentators tend to regard the number of sacrifices as a reflection of Thietmar’s general tendency to describe the Scandinavians and Slavs as wild and uncivilised people. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy, that Lejre early on played such a significant role in the mythology of the history of Denmark; and that Thietmar felt the need to name it the “national” centre. Later Danish and Icelandic chronicles fleshed the story out by recounting the heroic and legendary deeds of the Scyldings – Skjoldungerne – said to have had their royal seat there.

Nowadays, no one believes that these medieval chroniclers can be mined for exact information about the heroic deeds of these very early mythological kings. However, excavations at Lejre have continued to yield information about what was undoubtedly a remarkable elite centre in a period when Denmark was slowly turning into a proper medieval kingdom.

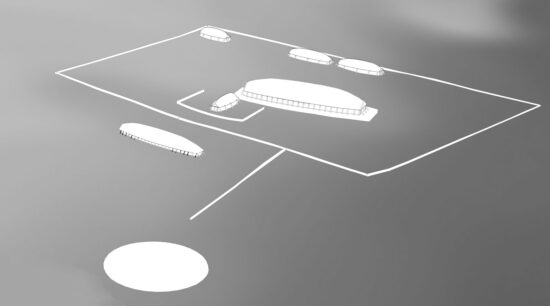

Looking at Gl. Lejre from the air, it immediately becomes apparent that the 6th-century settlement was located in an “old” landscape filled with ancestral mounds, some of which date back to the Bronze Age. To the east a small river borders up to a flat plain. This river, Kornerup, splits into two with Lejre Stream just east of the ancient settlement. Neither of these streams or tiny rivers is believed to have been navigable by anything except by prams. Between these two creeks spans a hilly isthmus are the remains of a Viking Age burial ground including the remains of four stone-ships from the first half of the 9th century. This necropolis was excavated in the second part of the 20th century. To the west of the village on a hilly slope a series of halls and other buildings were found.

To the west, a hilly landscape rises, covered in forests alternating with a more open landscape dominated by scrubby vegetation of oaks, elms, juniper and heather. When visiting – and you have plenty of time – it is especially recommended to take a tour of Særløse Overdrev (Særløse Commons) with ancient grassland recreating a sense of the timeless landscape.

Entering Gl. Lejre from the south, the road reaches the small village bordering on the banks of the western riverbed with the hilly isthmus to the left. Likely, the present village was at first a seasonal marketplace inhabited by craftsmen and merchants. On the hill to the left, several great halls have been excavated. An earlier settlement located up north dates to the 3rd – 5th centuries.

In itself the name Lejre is rare. Perhaps its original meaning was ‘shed’ or ‘tent’ and might have denoted a place where people got together and set camp. Today, the meaning of the Danish word “lejr” is still “camp-site” (spejderlejr= scout-camp).

First Phase: Fredshøj ca. 500 – 600

The first settlement (apart from some earlier and smaller houses) at Fredshøj can be dated to c. 500 – 600 and contained a large hall 47 m long, three-aisled construction with slightly curved walls and with a width of 7 meters at the centre and 5 meters at the ends. It was probably a rather high building fitted with a prominent gable, daubed and whitewashed. It must have been visible from afar by people travelling to the place along the road down below. Next to this hall were found the signs of yet another building. Nearby a stone heap was discovered which had been exposed to fire and with infill consisting of animal bones from primarily domesticated animals. 52% of the bones came from pigs, while 33% stemmed from cattle and the rest came from sheep and goats. Noticeable was the percentage of piglets signalling a surplus or elite economy. The same message is perhaps sent by the presence of the remains of a marten, which might have been hunted for the pelt. Remains of red and fallow deer plus ducks, geese and fish also contributed to the menu. Finally, some birds of prey seem to have been hunted, perhaps for the use of their feathers. It appears the animals were brought alive to the place and killed on-site near the stone heap – perhaps this was indeed a hörgr, a visible heap of stones used for sacrificing

The name of the location “Fredshøj” – Peace Barrow – signals a site cordoned off for judiciary dealings. With the hall set aside for the feasting. Nearby – to the west – a significant find of a golden bracteate from the 6th century plus an earlier find of a golden treasure signify the importance of the place as a cultic and political centre.

Dated to ca. 650 the remains of princely burial were excavated down by the river in a barrow called Grydehøj. Unfortunately the man and his grave-goods had been cremated, but a profusion of melted bronze and gold as well as sacrificed animals testify to his wealth.

Second Phase: Mysselhøjgård ca. 600 – 900

At the beginning of the 7th century, the site at Fredshøj was abandoned and moved approximately 50 metre south to the site, which is now called Mysselhøjgaard. This move was accompanied by the creation of a more complex settlement that had been divided into two parts, ditched and fenced. To the north the great hall was rebuilt, now on a magnificent platform constructed of stones and with an even more impressive gable. The hall was built on the slope, probably using this natural feature in the landscape to let the gable signal a very high and impressive building. Recently, the gate into the compound was discovered at the lowest point in the landscape. Measuring more than six metres and constructed with heavy posts, the gate obviously intended to enhance the “royal” power of the Lord of Lejre. Inside the fence, lesser houses were constructed to the south. To this was added the construction of a new stone heap. As the Mysselhøjgård-site was used for a longer period, the remains of animals appear to have been shifted around from time to time, when rebuilding and internal relocation took place.

The composition of the herd of animals is equal to that found at Fredshøj but expanded with several horses, dogs, wild hogs, beaver plus a more substantial element of deer. Probably these more wild “elements” reflect the reforestation that took place after the climate deterioration in the 6th century. Elsewhere on the site, pieces from the scull of a bear have been found. This might have come from an imported bearskin, perhaps used in a ritual context; as may be the case with another enigmatic find, a pierced piece of an antler that might have been fixed to a mask.

Dated to this period a significant find from a village called Gevninge up north on the road to the firth deserves notice: an “eye” from an elaborate helmet of the Sutton Hoo-type indicating Gevninge as the port to the “royal” site at Lejre. The “eye” is unique in a Danish context.

Third phase: Mysselhøjgaard c. 875 -1050

Finally, around 900, the hall was moved once more. Now located in the southern part of the hilly slope, the old site of the hall from phase two was given over to a burial ground. Interestingly, the grave of a 35 – 50-year-old man was found in the exact centre of the old – now defunct – hall. His grave was furnished with a fire steel, a knife with a handle wrapped in silver, and a fragment of what must have been a dress with gold-embroidered ornaments. The man had been buried in a coffin. Outside the defunct hall a number of other burials were found of mainly

elderly people, obviously belonging to the hardworking people at the bottom of society. Tom Christensen speculates that the site of the old hall was chosen as a “burial gift” to an important man in society. None of the minions buried in its periphery appears to have been the victims of a sacrificial killing. This, however, was the case in one of the other graves down by the river, where a 35 – 55 old man was buried with his hands and feet tied and his head chopped off. He was laid to rest together with a 25 – 40-year-old man. The impressive stone ship (80 – 100 metre long) nearby has been dated to the 10th century.

The hall itself changed slightly. Now the architecture became reminiscent of the last great halls of the “Trelleborg-Type” and got a new internal partitioning. It is during this period Jelling surfaced as a competing centre, while Roskilde soon after the year 1000 took over as regional centre at Zealand. Around 1050 it is obvious the aura surrounding Lejre had faded.

However – as is apparent from Thietmar – it also acquired an ill-reputed fame, lasting until the chroniclers in the 12th century began anew to retell the old heroic fairy tales. It may be significant that no church was ever built on site. The local church came to be erected two km to the south in the village of Allerslev. Perhaps there were too many heathen connotations still afoot?

SOURCES:

Lejre bag myten. De arkæologiske udgravninger.

Lejre bag myten. De arkæologiske udgravninger.

By Tom Christensen

Romu/Jysk Arkæologisk Selskab 2015

ISBN: 978 87 88415 96 4

Lejre beyond the Legend – the Archaeological Evidence

By Tom Christensen

In: Siedlungs- and Küstenforschung im südlichen Nordseegebiet (2010) Vol. 33, pp.237 -254.

Ed by John D. Niles

Arizona Studies in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (ASMAR 22)

Brepols 2007