The French king, Charles VII is known for his long reign and his success in ending the Hundred years’ War. But he also presided over the gradual employment of numerous bourgeois jurists and merchants paving the road for the shift from charismatic to bureaucratic leadership.

Charles VII was born in 1403 in Paris as the fifth son of the insane king, Charles VI of France and Isabeu of Bavari. He did not acquire the title of dauphin until 1417 when the last of his brothers died.

Charles belonged to the Valois dynasty, the family which ruled France from 1328 – 1589. This family descended from a cadet line established by a brother to Philip V, Charles IV. Both were beset with daughters, who were excluded from inheriting the French throne and hence used as pawns in securing alliances. One such – Charles IV’s sister Philippa of Hainault – had married the English king. As English law did not rule out that daughters might inherit, her son Edward III claimed the French throne. The magnates, however, preferred a cousin to the late king, the Count of Valois, who was elected as Philip VI. Eventually, this led to the hundred years’ war and a series of military and political disasters beginning with the annihilation of the French army at Crécy in 1346 and Poitiers in 1356, followed by a ravaged countryside plagued by pestilences and brigandage. After yet another military defeat at Agincourt in 1415, it took a lifetime of political wrangling and fiscal and administrative acumen to expel the English and forge the reunification of France and its peripheries. Central were the establishment of the independence of the French church securing the support of the ecclesiastical institutions as well as the establishment of a system of taxation, and a professional army. While the English experienced a series of internecine conflicts fiscal deroute ultimately ending in the War of Roses, the long reign of Charles VII secured a modicum of national unity.Life

Already as a child, Charles had experienced the dangers inherent in the tumultuous times, and in 1413 – the same year of his betrothal to his future wife, Mary of Anjou – rioting Parisians entered the Hôtel Saint-Paul, where he lived with his family. After these events, he went to live with his future mother-in-law, Yolande of Aragon at Tarascon. However, in 1416 (at the age of 13) he was back in Paris to be appointed Captain General of Paris and to participate in the Royal government.

After Charles was appointed dauphin in 1417 after the unexpected death of all his brothers, he entered the scene in one of the darkest moments in the history of France. His father, who was mentally ill, was at the centre of a series of struggles forged in the crucible of the Burgundians and the English. One key player was John the Fearless, who ruled the Burgundians. In 1407, he had the brother of the king, the Duke of Orleans murdered. This led to the eruption of a civil war between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians, who entered Paris a year later leading to the overnight flight of the dauphin, the future Charles VII. Retreating to the region south of the Loire, Charles became embroiled in the assassination of John the Fearless, leading to an ominous alliance between the Burgundians and the English. At the Treaty of Troyes in 1420, Charles was de facto disinherited. The treaty arranged for the marriage of Charles VI’s daughter Catherine of Valois to Henry V, who was elected regent of France and acknowledged as its future king. The Dauphin Charles was disinherited from the succession. Formally, the Treaty of Troyes was ratified by the Estates-General of France, and later that year Henry V entered Paris. Part of these events were played by a disinformation campaign claiming that the future Charles VII was the illegitimate offspring of his mother Isabeu of Bavaria and the king’s brother, the Duke of Orleans. Another argument for disinheriting the Dauphin was his part in the murder of the Duke of Burgundy, considered an “enormous crime”. In 1420, he was summoned to Paris to defend himself against these allegations. Failing to appear, he was condemned in a Parisian court as guilty of treason and sentenced to be disinherited and banished from France. A verdict, his father supported.

In 1422, however, the dauphin’s father, Charles VI and the English king, Henry V, died within months. While the latter left an infant, Henry VI, Charles was a youth in his prime and bent on reclaiming his inheritance. Nevertheless, it took the intervention of Joan of Arc (Jeanne d’Arc) and several military victories (at Orléans and Patay)before he was formally crowned at Reims in 1429. When Charles became king in 1422, he ruled only a third of the realm south of Loire, and was disparagingly called “The King of Bourges”.

Slowly, through deft politicking, he brought Burgundy to a separate peace in 1435. This led to his return to Paris in 1436, and the affirmation of royal control of the French church and the ecclesiastical revenues, formalised in the “Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges” in 1438. However, in 1439 he increased taxation and attempted to outlaw the private armies of the magnates and nobles in his realm, leading to half a decade of political rebellions, called the Praguerie (named after the corresponding rebellion by the Bohemian Hussites). These revolts were led by the Duke of Burgundy but involved his son, the future Louis X. The events led to a life-long enmity between the father and son.

After 1445, he was able to forge the ending of many of these hostilities, leading to a period of economic and organisational consolidation. This paved the way for a revitalisation and not least professionalisation of the French army, leading to a series of victories – Formigny in 1450, Bayonne in 1451, and Castillon in 1453.

Consolidating his authority, Charles deftly used diplomacy as well as the juridical system to reconcile the internal warring parties building upon several ruthless advisers, who helped him forge a more consolidated France, than the provincial corner, he was left with at the death of his father in 1422. In his lifetime, the growth of bureaucracy inspired numerous bourgeois to invest heavily in entering “the Noblesse de Robe” while busily acquiring positions in and income from the law courts and a juridical career. Convening with their enigmatic king, however, often brought ruin in its wake. During his long reign, numerous members of his entourage were not just set aside, but accused, brought before the courts of the realm, and condemned to loose everything.

Personal life

Charles was ten when he became betrothed to his future wife, Mary of Anjou, a daughter of his cousin. However, it was not until 1422, he could celebrate his marriage at Bourges. The next decade was marked by a series of financial troubles, and political as well as military setbacks and at one point the king actively planned to disband his government and move to Spain. As is known, the maid from Orleans changed this, by instilling courage and a new burst of energy resulting in the unction and coronation at Reims in 1429. After this, he exchanged his court of hangers-on with more skilled advisers, primarily the merchant Jacques Coeur, who became master of the mint until 1451, when he was expelled from court. At this point, his vast fortune was expropriated to consolidate the king’s coffers, and used to placate the so-called “bonne villes”, the provincial towns supporting his effort to rebuild the nation after the wars.

Charles is one of the very well-known kings of France, and yet he presents to us an enigmatic façade – shy, and perhaps sly, we occasionally get a glimpse of a ruthless operator when pondering the rank and file of advisors, which he used up during his long reign. It is perhaps characteristic that the king’s entourage was repeatedly castigated for its jobbery and corruption

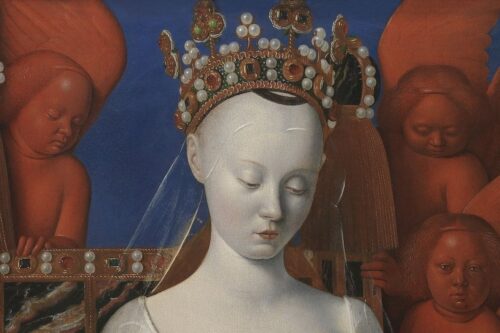

Some of his more important councillors were his mistresses, Agnes Sorel, and after her death, Antoinette de Maignelay, with whom he enjoyed a prudent, yet luxurious life surrounded by the pleasures provided by artists and intellectuals. However, he also enjoyed an amicable friendship with his queen, with whom he fathered fourteen children, of which five survived their parents. With Agnès Sorel, he sired four children, one of which died at birth.

Arts and court culture

The courts at Bourges, Chinon and elsewhere were never as glittering as the brilliant court in Burgundy. Nevertheless, after the 1440s, distinct employment of artists recording the central ritualised events such as the adventus of the king into one of the “bonne villes” or his participation in “parlements” took place.

Thus, the main French artist in the epoque, Fouquet, portrayed the king in numerous guises – entering the parliament and sitting as judge at the trial of one of his dukes, or as personating as one of the three magi in a nativity scene in a prayer book. In this, his advisors and councillors followed suit sponsoring artists while having their portraits painted or piously included in the side panels of triptychs featuring crucifixion scenes. The inclusion of portraits in the miniatures created for sumptuous manuscripts was part of this new trend. A gaudy example of this is the portrait in his Book of Hours, of the arriviste, Simon de Varie, one of the many “king’s men” busy building the new bureaucratic traditions of leadership at the king’s court while posing a an enobled member of the old world.

FEATURED PHOTO:

Entree of Charles VII to Rouen. © BnF Bibliothèque nationale de France, NAF 4811, fol. 70v.

READ MORE: